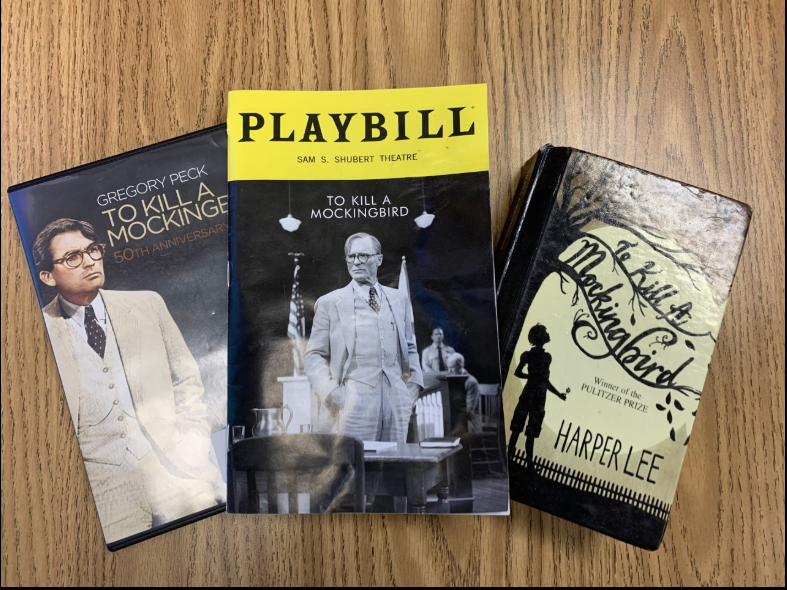

To Kill a Mockingbird: From the Shelf to the Screen to the Stage

To Kill a Mockingbird, an influential novel written by Harper Lee, has been adapted into a Broadway show. Being a fan of Lee’s novel (and the film adaptation that succeeded it), I was excited to witness its newest adaptation. I arrived at the theatre, seats crowded with others who were, presumably, also fans of the novel. As the theatre lights dimmed, I prepared myself for another great version of this literary masterpiece. Sadly, my expectations were not met.

The novel and the film are detailed enough that they provide fleshed-out characters and strong character arcs. However, the play was lacking in this. Scout, portrayed by Nina Grollman, does not undergo any character development throughout this adaptation. In the novel and film, Scout is introduced as a naïve child, who gains empathy and maturity after witnessing the Tom Robinson case. Scout’s character development is emphasized less in the play than it is in the film and novel. This is most likely because the play is presented from a third-person perspective, unlike the novel, which is strictly from Scout’s point of view. The change in perspective gives the play a less personal feeling, subsequently giving the viewer less opportunity to understand and relate to Scout’s character.

Consistent characterization is exempt from the play as well, as shown by its versions of Calpurnia, Dill, and Scout. In the play, Calpurnia (Lisagay Hamilton) has a rocky relationship with Atticus Finch (Ed Harris). Most of their scenes together are filled with passive-aggressive remarks from Calpurnia, and Atticus making failed attempts to reason with her. This contrasts with her characterization in the other versions, in which she and Atticus have a camaraderie. Scout and Dill (Taylor Trensch) are also subject to conflicting characterization throughout the play. Scout and Dill’s characters are more immature than in the previous versions, contrasting with the play and the film. Dill does not undergo any significant character development, and one of his main purposes is simply comic relief. In the other versions, the children are innocent yet somewhat mature, and each character is able to breathe life into the story.

The discrepancies between the other mediums and the play continue beyond the characterization. The chronology of the scenes is one example of this. The scenes in the play rapidly change from the court room interior to scenes of Jem, Scout, and Dill playing together. This seems like an attempt to hold the viewers’ attention and to not bombard them with slightly tedious court scenes; however, this makes the scenes feel choppy and awkward. Another flaw is the attempted fusion and exemption of characters. In the play, Link Deas’ and Dolphus Raymond’s character traits are combined to create one character. Although this is not an extreme discrepancy, it feels strange. When combining characters, some of both characters’ traits are lost, and their original purpose in the scene is lost.

Although the performance had its flaws, it was also able to excel in some areas, most notably set design and acting. The set design is structured so quickly and beautifully that transitions are made between the Finch residence and the courtroom. The actors are all able to play their characters believably and with relatability. This play was decent, but when it comes to classics, I think enthusiasts of To Kill a Mockingbird would be better off turning their attention to the shelves and the silver screen.

Hi! I'm a member of the Class of 2023. In my free time, I write and play piano. I am so excited to be working for Horizon!