Bali’s Burden

As the Indonesian island awaits eruption, Bali’s hopes are bittersweet

After more than 50 years, the Indonesian island of Bali is under high alert as an active volcano begins to show signs of a larger, possible eruption.

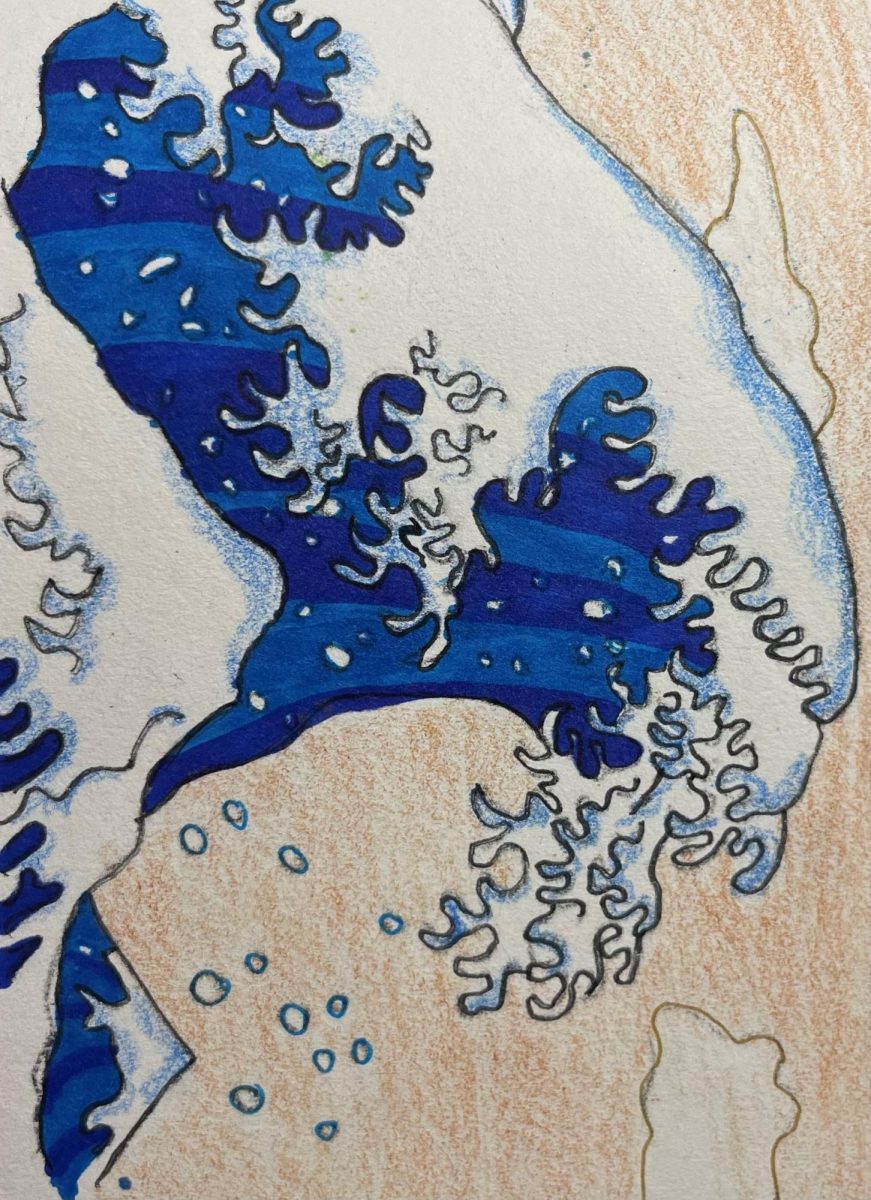

Known for its tourism and agricultural industries, volcanic activity certainly is not new to Bali. In part due to its position along the infamous Ring of Fire, Indonesia is home to more active volcanic sites than any other country on the planet – so much so that “more than one eruption occurs at any given time,” Erik Klemetti, a geoscientist at Denison University, told USA TODAY.

Still, despite the regularity of Indonesia’s volcanoes, the eruption of Bali’s highest summit, Mt Agung, has not been cordial to the island’s inhabitants.

Since November 22, Agung has spewed massive plumes of smoke and ash, grounding flights out of Ngurah Rai International Airport, as well as prompting the evacuation of over 100,000 people who live in a six-mile perimeter of the mountain. To make matters worse, large tremors have also been noticed along Bali’s eastern half (an area encompassing Mt. Agung), ominous indications that underground magma is on the move. Once enough magma builds, excelling the Agung’s capacity, the volcano will erupt, exploding out debris up to six miles into the sky.

“The volcanic eruption has now moved on to the next, more severe, pragmatic eruption phase, where highly viscous lava can trap gasses under pressure, potentially leading to an explosion,” Mark Tingay, a geologist at the University of Adelaide’s Australian School of Petroleum, said in a statement to CNN.

Despite most of Bali’s tourist destinations lying far outside evacuated areas, fear of soon-to-come catastrophe and airport shutdowns have continued to cripple the local economy as Bali’s eruption is prolonged. Indonesia’s Minister of Tourism, Arief Yahya, estimated in a statement with the New York Times that Bali could stand to lose somewhere upwards of $665 million from the current crisis.

In response to the recent economic downturn, some Balinese citizens have even drawn comparison to events following the 2002 bombing of a popular nightclub in the Kuta district that killed 202 people, the vast majority tourists. Yet another attack occurred in 2005, undertaken by Muslim suicide bombers. Since then, Bali’s economy for tourism has been on a slow recovery, reaching an apex in 2013.

Tjokorda Oka Artha Ardhana Sukawati, one of Bali’s largest figures in tourism, said the island’s hotel occupancy has dropped to only 20 percent, a forty-percent drop from last year’s lead-up to the holiday season.

Others fear Agung’s most recent activity could parallel a similar eruption from Bali’s past. In March of 1963, Mt. Agung erupted, releasing massive poisonous gas clouds known as pyroclastic flows that killed more than 1,100 people.

Still, not everyone sees the situation in the same light. What once would have been a crowded holiday destination is now rendered idyllic, as tourists stranded by cancelled flights take advantage of the tranquility. “In our selfishness, we enjoy it,” Ms. Sorum, 27, said of the sparsely visited shoreline in an interview with the New York Times.

I am a sophomore contributor to Horizon, a New York resident since 2002, and child of the New Millenium.