LHS Needs a New Heating and Cooling System More Than Ever

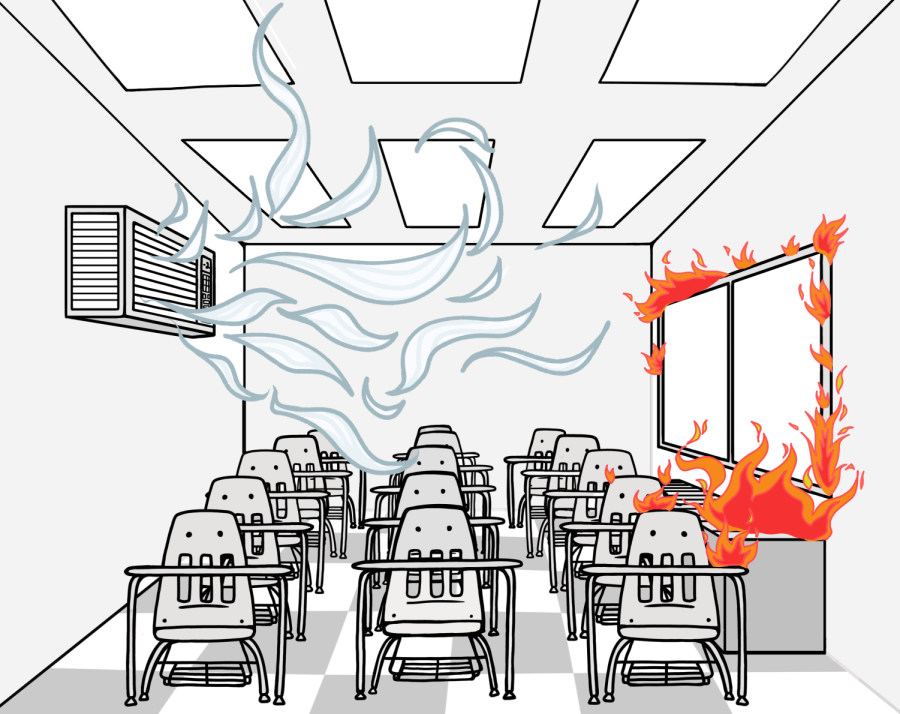

The date: December 21. The occasion: the winter solstice. Because it is a Wednesday, students pile into LHS, braving the winter chill and hoping to enjoy cozy classrooms. Some of these students are inevitably disappointed. Upon reaching their destinations, they will find the air conditioning is on full blast with the windows open. The reason: the classroom was, the teachers claim, “boiling hot” when they arrived. Many pull out extra sweaters and hot drinks to stay warm; class, it seems, will be a lot colder than previously thought. In other rooms, the doors and windows stay shut, turning the environment practically into a stifling sauna. The “boiling hot” conditions are very much a struggle.

Much of LHS deals with the problematic heating and cooling system daily, especially during the colder months. The older sections of the building have it worst of all. The science wing (or “banana wing”) is one of the hottest parts of the building, and not in a good way. Most of the temperature-regulation facilities have not been updated in decades, and the classrooms are disproportionately affected. Higher floors are often very warm as well; given that heat rises, all energy generated from floors below flows into the third and third-and-a-half floors. Classrooms that get full sun also become quite warm. Social studies teacher John Cornicello, whose classroom is on the third floor, can attest to this frustration: “I have been known to put the air conditioner on during the winter,” he said, further commenting on how the sun makes his classroom very warm. “I know that it may be February outside, but it often feels like June in my classroom.”

Not only does the excessive use of heat in classrooms make the students and staff uncomfortable, but it also contributes to a large loss in energy. Typically, there is one heater and one in-wall air conditioner per classroom. Multiplied by the large number of rooms in LHS, there is already a very large energy bill. But as doors and windows are left open, much of that generated energy disappears–and it is not just the warm air. When the air conditioners are left on with the doors and windows open, the cold air leaves as well. This loss of energy is costly, both for the district’s wallet and for the planet. LHS, as it stands, contributes to the estimated 72 million metric tons of carbon dioxide U.S. schools emit each year, according to The U.S. Department of Energy (energy.gov).

So, what is a school to do? To avoid further discomfort and loss of energy, many believe centralizing air conditioning and heating is the answer. If this system replaces the current inefficient system, it will do away with the rumbling wall AC units and provide more overall comfort. Principal Matthew Sarosy thinks this is one of most ideal solutions but added that it would require voter approval due to the cost. English teacher Jill Garfunkel, who notices that each room’s temperature can feel “drastically different” from another, would like a system that is more specific to each class. “It would be nice to be able to self-control by room,” she said, commenting on how she would prefer her room to be “nice and toasty.” Cornicello, too, would like to have greater control, wishing to regulate his radiator more easily. Junior Chloe Singh does not have any specific concerns regarding the system but appreciates when “it’s a cold winter day, and the building is a nice temperature when you walk in.”

Hey you! Thanks for checking out my profile. I am a member of the Class of 2024 and a storyteller at heart. I love to spend time with my family and friends,...