“What Would Walt Think?” Comparing Disney’s Currents to Its Classics

The Walt Disney Company has gone through significant evolution in its lifetime. Founded in 1923 by Walt Disney, the company grew gradually in both film quality and popularity, moving from soundless, black-and-white shorts to full-length original films accompanied by beautiful scores. Disney has experienced much success over the past near century. In fact, at D23 Expo, the annual convention of the official Disney fan club, the Walt Disney Company introduced “Disney 100 Years of Wonder,” a program that recognizes Disney’s centennial and kicks off another century of anticipated success with new films and series as well as additions to the company’s theme parks. But my question is, with all its transformation, is Disney continuing to soar above the wishing stars with Tinker Bell and Peter Pan, or has it started to run out of pixie dust and drop towards the ground?

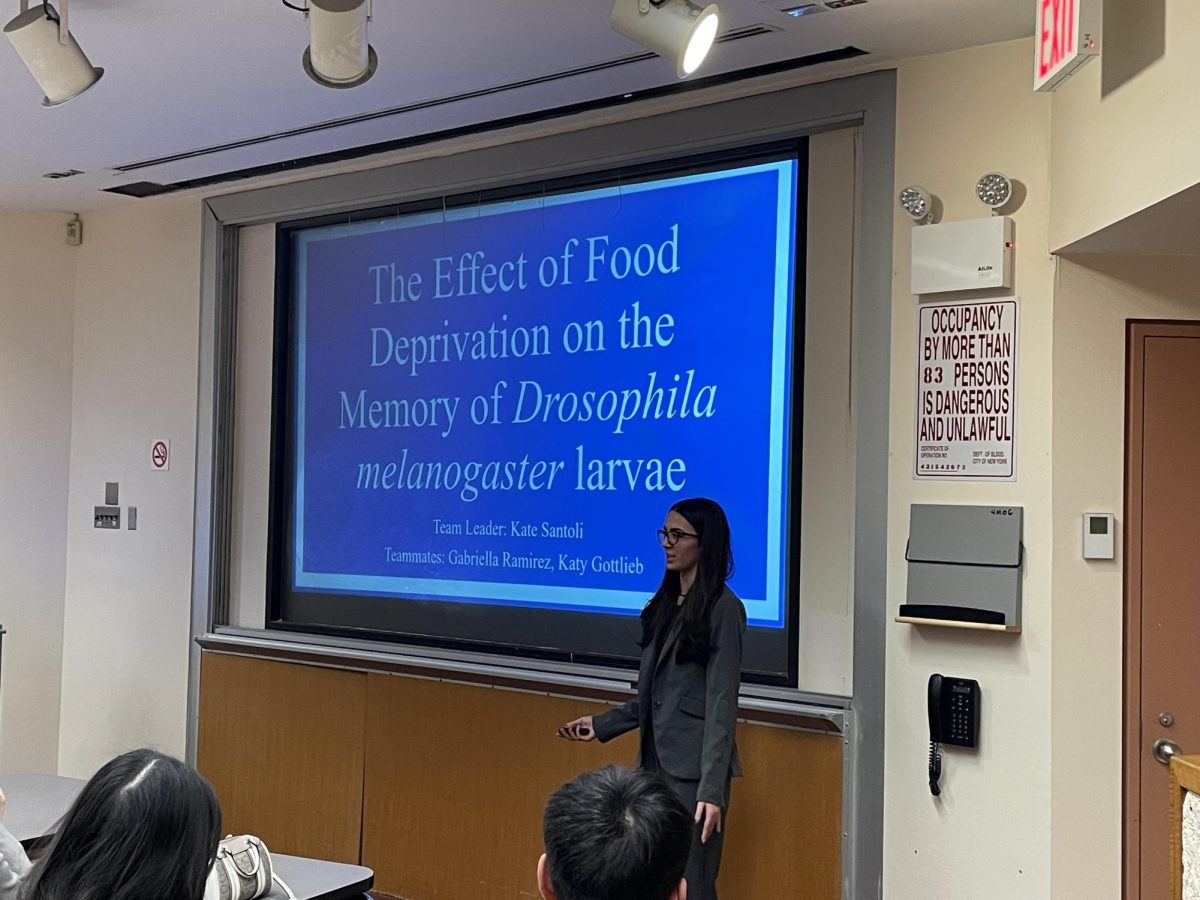

I consider myself a Disney fan. But lately, my respect for the company has declined. The straw that broke the camel’s back and made me think more deeply about where Disney has gone was the live-action remake of Pinocchio, which was released on Disney+ in September of 2022. The original, animated Pinocchio from 1940 shows Pinocchio’s meaningful journey to become a “real boy” as he learns to be “brave, truthful, and unselfish” as well as obedient and loyal to his endearing, puppet-making father, Geppetto. Roger Ebert, esteemed film critic, wrote in his 1998 review of Pinocchio (1940) on the Roger Ebert website, “Has popular culture ever produced a more unforgettable parable about the dangers of telling a lie? The story is just plain wonderful” (RogerEbert.com). However, the sincere, lovable puppet from the original is not done justice by the 2022 live action. He seems, quite ironically, to be much more two-dimensional. Though Pinocchio as a character is meant to be young and sometimes unwise as he tries making his own decisions, the live action Pinocchio does not seem to learn from his actions and choices, unlike the original. For example, in the 1940 version, Pinocchio, trapped in a cage by the malicious Stromboli, sees the Blue Fairy descending towards him and is so ashamed of the predicament he has gotten himself into that he tries to hide his face from her. When she arrives, he tells lies to cover up his wrong choices, but his nose begins to grow with each addition to his lie. Realizing his mistakes, he promises to be better, and the Blue Fairy grants him forgiveness and a second chance. Contrastingly, in the 2022 version, rather than meeting the Blue Fairy and feeling ashamed, Pinocchio loses his trust in people, blaming his situation for his problems instead of his own poor choices. Additionally, when he lies to Jiminy Cricket (instead of the fairy), he does not seem to feel much remorse, but exploits his nose-growing ability to obtain the key to his cage, giving a couple of lighthearted apologies to Jiminy to return his nose to normal. There is a distinct lack of personal responsibility, regret, and change. Also, certain twists in the newer version that differentiate it from the old, the purpose of which was perhaps to modernize the film, “too often feel empty and add no insight,” according to Christy Lemire on RogerEbert.com. Though the comparison between the original Pinocchio and its remake is one of the starkest examples, it reflects a decline in Disney’s films that is visible not only in certain live-action adaptations, but also in some of its latest originals.

Disney’s “classics” that have become defined symbols of the company were mostly released in the 20th century. A notable characteristic that sets them apart from Disney’s more recent releases is that they were enjoyed by such a wide audience. They were beloved by families, while also being relatable for the individual watcher. Captivating adults as well as children seemed to be a goal of Walt Disney himself, who once said, “That’s the real trouble with the world, too many people grow up.” An article on Encyclopedia Britannica’s website (Britannica.com) about the life of Walt Disney writes that he “develop[ed] well-loved amusements for ‘children of all ages’ throughout the world” and describes him as “a creator of entertainment for an almost unlimited public.” Movies that fall into this category include Beauty and the Beast (1990), Aladdin (1992), and The Lion King (1994).

The way I see it, the Walt Disney Company’s entertainment now seems to be for a much more limited public. Recent originals like Raya and the Last Dragon (2021) seem to be geared much more towards young children. The animation is incredibly colorful and vibrant, and the films are often very fast paced, which can be attractive and appealing for children; however, behind the visuals, the films lack depth. The themes feel like clichés and platitudes, the characters and relationships recycled and too familiar. Of course, adults can watch these films with their kids, but probably would not be nearly as attached to them. Disney’s audiences are more divided, leaving behind the unity the older films had. Family movies that are actually appealing to the whole family are fewer and farther between.

As for live-action remakes of animated classics, sometimes live-action is not always the best action. I do not mean to disparage all of Disney’s live-action versions of old films; I like many of them and appreciate seeing the old movies in another style. However, remaking the old films into live-action adaptations is not all pros; there are many negative effects that do not enhance the original stories, but detract from them. Fascinatingly and ironically, in Ebert’s review for the animated The Lion King (1992) also on RogerEbert.com, he noted the implementation of technology in the animation while saying, “The early Disney cartoons were, of course, painstakingly animated by hand. There has been a lot of talk recently about computerized animation, as if a computer program could somehow create a movie. Not so.” And yet, almost 30 years later, this is exactly what was done for that exact movie. Junior Olivia Lanteri seems to agree with Ebert; she commented, “I think that live-action adaptations of animation should never be made. You can convey so much in animation that you can’t execute well in any other art form; because of this, the adaptations are vastly underwhelming and are often a lazy cash grab.” The original The Lion King (1994) received an impressive 8.5 out of 10 on IMDB, one of the highest scores of all the classic Disney movies. Its remake only received a 6.8, which is still too high. The remake seemed to be almost an exact replica of the original, with perhaps more cheesy jokes. In a review of The Lion King (2019) on The Guardian’s website, titled “The Lion King Review – Resplendent But Pointless,” critic Mark Kermode seems to agree somewhat with Ebert’s qualms with entirely computerized movies, expressing, “It’s one thing seeing a cartoon lion sing, but watching photorealist recreations of animals speaking and bursting into song is altogether harder to swallow” (TheGuardian.com). Kermode further explains that the Broadway production of The Lion King was so successful because it “required the audience to use their imagination,” but “There’s little space left for that kind of collaborative experience here [in the live-action version], as every detail is filled in, down to the very last pixel” (TheGuardian.com). Seeing personified animals in wonderous lands feels much more charming when viewers are transported into entirely different, animated world of imagination, whereas bringing these exotic elements into our own world with live-action films can feel unnatural and awkward. Perhaps by making its old movies so realistic, Disney has detracted from the magic and creativity it has always been known for.

With so many changes being seen in the Walt Disney Company, the question that comes to mind is, what would Walt himself think about his company as it is today? When asked this question, Lanteri responded, “I think Walt would have been very pleased to see how his humble animation studio turned into such a successful business, but I also think that he would be heartbroken to see how profit-driven the company has become. Disney used to be a company brimming with new ideas, interesting projects, and passion – now, it’s become a monopoly and exploits every property it can get its hands on.” Some Disney fans online seem to have related opinions. In an article titled “What Would Walt Disney Think of Disney Today?” on Quora.com, Paul Schnebelen commented, “I’m sure [Walt Disney] would have been happy to see that his little movie studio and theme park had grown to become one of the world’s largest companies as well as one of its largest media conglomerates.” However, in the same article, Schnebelen went on to say, “I’m not sure he’d be pleased to see that Disney has become more and more dependent on ‘re-imagining’ its older properties to maintain its success, instead of taking some chances and fostering the creativity to come up with more and better projects in-house” (Quora.com). Others’ thoughts on Walt’s perspectives are more confined to the negative. Jaiden Moreno, a senior, expressed, “I do not think he would like the more progressive films.” Xia Yue Liang, in the aforementioned Quora article, wrote, “He would probably be as disappointed as I am. All they do now is sequels and remakes. He was all for create and invent, not recycle” (Quora.com). Personally, I agree that the growth of Disney and its theme parks would excite Walt if he could see it today, but that he would disapprove of the path that Disney’s films have gone down. Even so, I think he would give everyone in the company a second chance, a theme apparent in so many Disney classics, and perhaps help to bring the value, both morally and cinematically, back into the films.

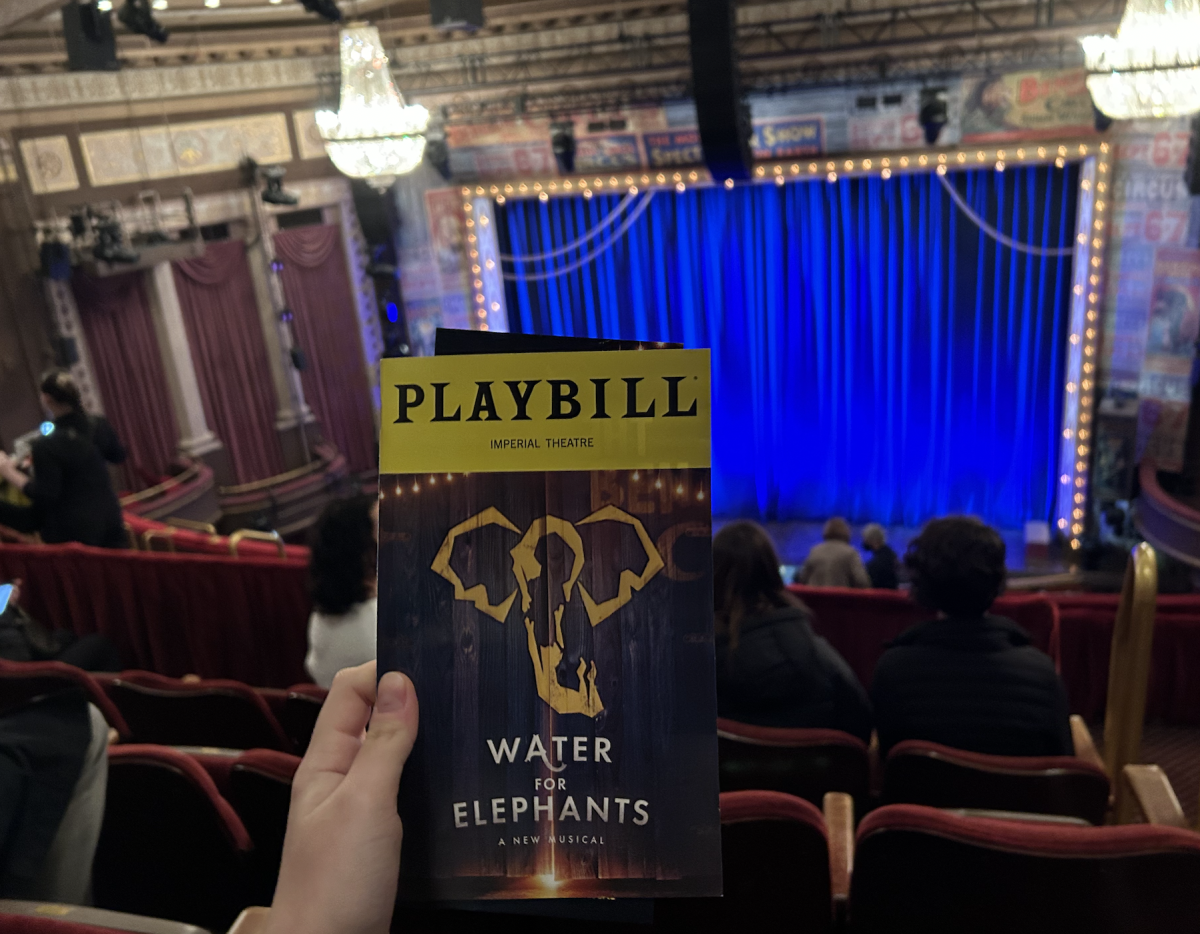

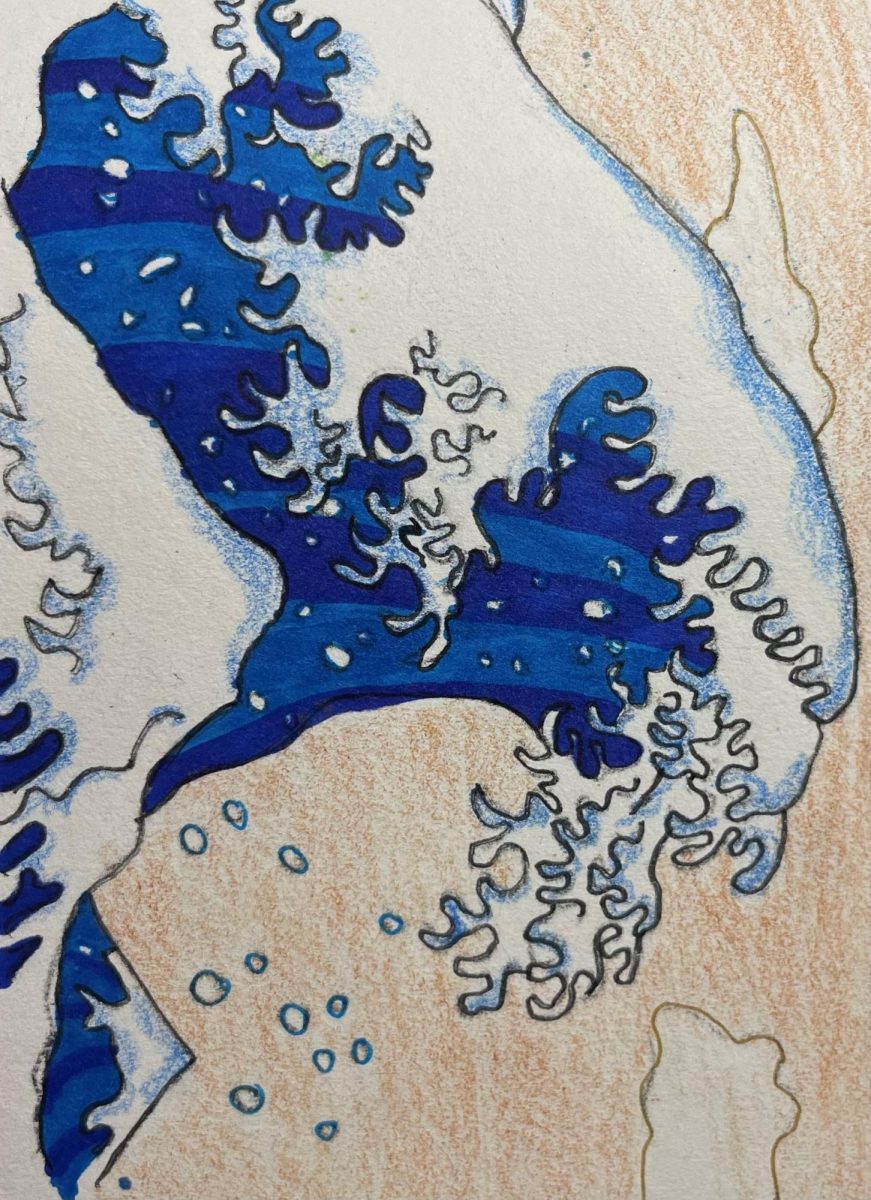

But Disney has not completely abandoned the foundation that Walt first built it upon, even if it appears to have strayed from it. The company seems to continuously strive to maintain its motifs of dreams and magic, whether its new films do so successfully or not. In an article on The Walt Disney Company’s website (TheWaltDisneyCompany.com) recapping D23 Expo, Bob Chapek is quoted as saying, “It’s an awesome responsibility to lead Disney as we begin our second century of telling stories and creating magic that will endure for another 100 years.” Chapek’s statement seems to align with Walt’s original hopes, as does the summary of a new movie, Wish, which is to be released in November of 2023. As explained in the article, Wish “explores how the wishing star that so many Disney characters wished upon came to be” and that the visuals are “inspired by watercolor illustrations of fairytales that fascinated Walt Disney…” (TheWaltDisneyCompany.com). Such descriptions bring the hope that Wish, as well as the films that follow, will honor both the motifs of some of Disney’s beloved originals (including Pinocchio, with its basis of wishing upon a star) as well as the principles and inspirations of its founder, Walt Disney.

I am a member of the class of 2024 and a co-editor-in-chief of Horizon's online publication. I have one dog and eleven siblings, and I love to read!