March Mammal Madness

Each year, basketball fans meticulously create a bracket for the March Madness tournament, predicting which college basketball teams will make it to the National Championship. This year, LHS students were invited to partake in the 10th annual March Mammal Madness, which also involves the meticulous creation of a bracket but features the organisms of the world instead of basketball teams.

March Mammal Madness was created by Professor Katie Hinde and her colleagues from Arizona State University in 2013. Since then, it has become a global phenomenon, attracting children, students, museums, professors, teachers, and animal lovers.

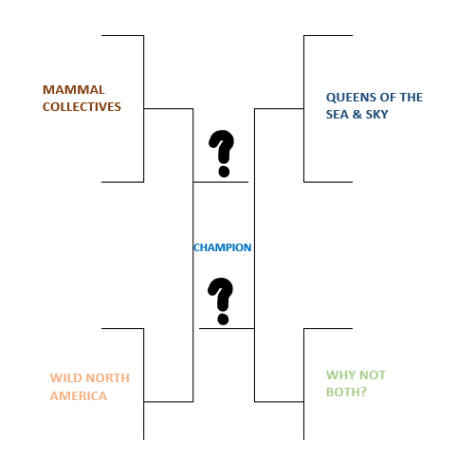

Similarly to March Madness, participants predict which organism they think will “win” in a fictional game or battle against one another. There are four groups of animals on the bracket; this year, the categories were Mammal Collectives, Wild North America, Queens of the Sea and Sky, and “Why Not Both?”

Each animal is given a number to represent its “seeding.” No prior knowledge is needed, but participants are encouraged to research each combatant’s attacks, armor, fight style, motivations, and special skills to compose the most accurate bracket. Numerous resources are given on the March Mammal Madness website to aid in this research. The researchers at the head of the competition take all these factors into account and then use a random number generator to determine the outcome.

Throughout March Mammal Madness, there are many upsets, as with March Madness. An upset occurs when a low-ranked organism defeats a higher-ranked organism; for this reason, participants are warned to not always pick the higher “seeded” teams. For example, an animal may be battling in an ecosystem that is different from its natural habitat, could get injured in a previous round, or may hide or run away, which are both considered forfeiting and mean the animal lost that round. There are also “Cinderella” organisms that are low-ranked but progressively move on, defeating higher-ranked teams.

Sophomore Mary Costello, who is a first-year competitor in March Mammal Madness, considered a number of factors about the organisms to decide which ones would be victorious. “I googled the speed of each animal going up against each other and used that as my basis for my guesses,” she explained. “I also took into account the weight, build, and natural environments of each animal.”

Sophomore Isabella Martinez, another first-year competitor in March Mammal Madness, also made sure to do thorough research when composing her bracket. “I looked up pictures of each animal and compared their characteristics,” Martinez said.

At the beginning of the competition, the battles are located in the preferred habitat of the better-ranked combatant. As the tournament progresses, the location is chosen among four random ecosystems, which are announced right before the battle. This causes many upsets to brackets. Additionally, the battles are not always to the death. Sometimes an animal wins by displacing the other animal at its feeding location, or a powerful organism does not attack because it is not motivated or provoked, causing the less-powerful organism to win. Small cuts or bites can also cause animals to back down.

A new feature was recently introduced, allowing “teams” of animals in the Mammal Collectives category to face off. This category places unique groups of animals against each other, often with surprising titles, such as an embarrassment of pandas facing off against a town of prairie dogs. Previously, only singular animals would battle each other.

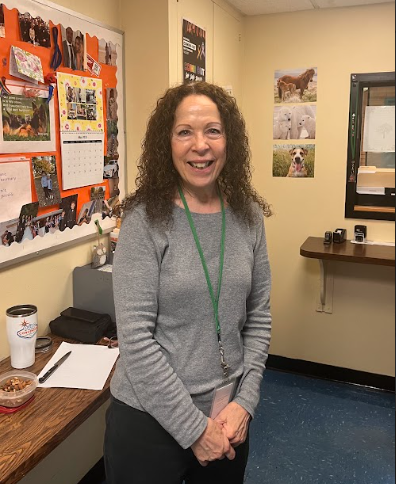

Science Research teacher Kathleen McAuley said she is excited about this new feature. “It’ll be so interesting to see how group dynamics may change outcomes,” she commented.

In round one of the Mammal Collectives category, the pride of lionesses and the labor of moles battled each other. Moles are not social creatures and prefer to spend time digging alone, whereas the lionesses are sociable creatures. The mole attempted to scurry away from the lioness, but the lioness refused to back down as the mole became its prey. The lioness pounced on the mole, ultimately winning the battle.

The battle between the embarrassment of pandas and the town of prairie dogs took place in the largest remaining habitat of giant pandas, the Wolong Nature Reserve in the Qionglai Mountains of China. The prairie dogs were not in their natural habitat and, thus, could not dig tunnels in the wet, dense bamboo forest, allowing the embarrassment of pandas to take the win. The other advancers in round one of Mammal Collectives included a cauldron of bats, a conspiracy of lemurs, and a wisdom of wombats, among others.

In round one of the “Why Not Both?” category, the walrus, echidna, serval, pangolin, therapsid, salamander, hairy frog, and swordfish defeated their opponents and advanced on to round two.

In the Queens of the Sea and Sky battle between the orca and the common prawn (a type of shrimp), the orca emerged victorious. Orcas are apex predators and are not interested in the shrimp; however, the common prawn swam away, thus “forfeiting” that challenge.

In the battle between the Arctic tern and the Indian fruit bat, the Indian fruit bat was crowned the winner. March is a migration period for the Arctic tern; thus, it showed no interest in the Indian fruit bat flying past it to its Northern breeding and nesting grounds. This marked another upset in the tournament so far. In the Queens of the Sea and Sky rounds, the sea snake, map turtle, octopus, parrot, sea eagle, and monk seal also advanced on to round two.

The competition between the animals continued with updates being posted through battle animations on the official March Mammal Madness website. The winner for LHS was determined by the following point system: one point for correct wild card winner, one point for each correct round one winner, two points for each correct round two (“sweet sixteen”) winner, three points for each correct round three (“elite trait”) winners, five points for each correct round four (“final roar”) winners, eight points for correct round five winners, and 13 points for the correct champion, with a maximum of 138 points.

McAuley shared that one of her favorite parts of March Mammal Madness is that the competition is accessible to everyone. “I’ve heard of kindergartners making predictions, going all the way up to students getting their grandparents involved,” McAuley said. She added, “The enthusiasm is contagious, and I’m so excited LHS students are getting into the MMM competition this year.” McAuley shared her pleasure in hearing students talk about March Mammal Madness with their friends in the cafeteria.

For a LHS student to participate, brackets had to be submitted by Mar. 11. To be involved, one simply had to scan one of the QR codes throughout the building to submit their bracket for a chance to have the champion bracket, accumulating the most points.