The United Nations Make Progress at COP26 Summit

In recent years, the belief that the world is being changed for the worse by global warming has become more widespread; from devastating heatwaves to torrential floods, it seems there is no end in sight for these so-called “natural” disasters wreaking havoc on the earth, and according to Wired magazine (wired.com), a team of mathematicians predict that “when it comes to climate change, things might have to get demonstrably worse before they can get better.”

The pressure is on for politicians and world leaders to come together to solve this tremendous problem. Progress, while not meeting everyone’s expectations, was made at the United Nations’ (U.N.) annual COP climate summit, this time held in Glasgow, Scotland, from Oct. 31 to Nov. 12.

A top priority of the summit, addressed by U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres, was for the world to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius, or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, above pre-industrial levels. The agreement outlined steps the world needs to take in order to meet this demand, first established at the 2015 Paris Climate Accord. Such steps include the severe reduction of carbon dioxide levels within this decade and curbing the use of methane, another potent greenhouse gas, as stated by The New York Times (nytimes.com).

The environmental minister of the Maldives, Shauna Aminath, echoed a sentiment of the summit, saying there is not enough being done for smaller, less-wealthy countries. “What looks balanced and pragmatic to other parties will not help the Maldives adapt in time,” Aminath said, according to The New York Times.

Sophomore Amelia Doyle does not think that this agreement will contain global warming fast enough. “The agreements were not major enough to help stop the warming [of the planet] by 1.5 degrees Celsius,” she said. “It is frustrating how people in power don’t seem at all worried around what has happened to the earth.”

On the other hand, junior Allison Anemone believes that countries have the capability to accomplish this difficult task, but only if they work together in agreement. “Only six out of 10 of the largest methane emitters are part of the Global Methane Pledge,” she said. “Without the four countries, accomplishing their task would be difficult without countries working together.”

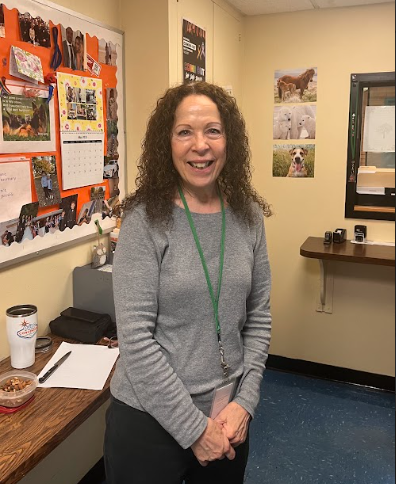

Educator Marisa Lanteri believes the agreement is a good place to start, but views it as an “ongoing, ever changing plan.” She claims that the plan “will need to have several modifications and changes as our climate changes.”

Another significant question posed at the summit was left unresolved: Which countries need to cut their emissions, and by how much? A war of words and promises brewed between rich and poorer nations; as stated by The New York Times, rich countries account for 50% of all planet-warming greenhouse gases created by fossil fuels since the start of the Industrial Revolution and have urged poorer countries like India and Indonesia to quicken their direction away from fossil fuels. However, many of these impoverished nations say that they “lack the financial resources to do so,” and point out that the aid many rich countries promised to contribute has fallen short by tens of billions of dollars, annually. Without this needed aid, poorer countries have fewer resources to switch to green energy and resist catastrophic natural disasters in the future.

Another complex and delicate subject touched on was the fast-growing carbon offset industry. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, carbon offsets refers to “an action or activity that compensates for the emission of carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.” Many of these actions and activities involve directly paying for the compensation of one’s carbon footprint, enabling many negotiators to announce a major deal on how to regulate this market. Many poor and vulnerable countries claimed a right to a slice of the market’s earnings, explaining how they need the funds to adapt to climate change to ensure a truly global reduction in emissions.

Multiple other decisions were made as well: the U.S. and China made a surprise joint agreement to further reduce emissions this decade; more than 100 countries pledged to decrease deforestation and methane emission by 2030; and, India promised to reach “net-zero” emissions by 2070. Many of these agreements rest on the trust that these countries will keep their promises.

When asked if she thought these promises will be kept, Doyle expressed a believe-it-once-seen attitude. “In the past, most countries have failed to live up to their promises, so I don’t think all these promises will be met,” she said. “But, the clock is ticking, and we are running out of time, so actions must be taken. Words don’t go a long way when there is no action to back them up.”

Anemone views the situation differently and believes the promises will be kept. “During the last one-and a-half years, pollution and climate change have improved a great amount because of COVID-19,” she said. “People now know that these goals are possible, and we need to act now to help the planet before it is too late.”

Lanteri is also hopeful that the promises will be kept. “A lot of times, politicians say one thing and do another,” she said. “However, in these days and times, more and more people are becoming more aware and vigilant of the threats to our world if we don’t take care of it. They are more cognizant of thinking about the future of our global climate and how it can, and will, affect them and many generations to come.”

On the final day of the summit, many goals were established for future conferences. This entailed governments promising to return next year to develop bigger and better agreements to curb global warming, and rich nations promising to at least double their funding for more climate-vulnerable nations.

Doyle expressed urgent hope for next year’s summit, especially because of the lack of time left to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius. However, she also emphasized the importance of being proactive today, as the agreements for future conferences made would “not be enough to get climate change under control in time.”

Hey you! Thanks for checking out my profile. I am a member of the Class of 2024 and a storyteller at heart. I love to spend time with my family and friends,...