“My Friend Elijah”

For Elijah, noon on Sundays begins with a pounding on his door, as opposed to traditional greetings. Thick sheets of ice cover his mother’s heart, and perhaps her eyes too, as she lacks the empathy to see the state of her son. She believes Elijah sleeps till noon on the Sabbath because of laziness and that confession will cure-all. But, she has yet to understand and get him the help he needs; I know this because he has not seen a therapist yet, and he hasn’t been replying to my texts for a week now. Nonetheless, I still see him at church every Sunday praying for peace, friends, freedom, death, and who knows what else.

Mondays are hard for everyone — that’s true. But no one suffers from them more than Elijah; the speech his mother gives him after church about sleeping late tires him out for a solid day afterward. Sometimes, he skips school on Monday altogether by way of playing some trick on her. But, when his deception fails, and he does come to school, he dresses in the “giving up” uniform: a sweatshirt and sweatpant that probably haven’t been washed in weeks. Before, he was like every other boy, sporting shiny new Jordan’s and a trendy hairstyle. It only took the finalization of his parents’ divorce to change him, school gossip says. Since then, his style has been down the drain. “What a shame,” they say, “what a shame.”

But our friend group, Lindsay, Donovan, and I, theorize that the change in Elijah is more than just fashion. Elijah ignoring texts for a week now has become normal for all of us. While sipping a soda, Lindsay mentions the possibility of Elijah being depressed. We all knew this discussion was a long time coming, since the social worker keeps on asking us if we’ve heard from Elijah. I Google the search term “depression,” aware that this is one of the more reasonable searches I’ve made at lunchtime: “‘Symptoms include tiredness and lack of energy, sleeping too much, poor attendance at school, avoidance of social interaction,’” I read off of the webpage. “It’s like we’ve stumbled on his medical records,” I say. Below the article, I see stories of depression survivors, mental breakdowns, physical harm, and suicide attempts. I close the laptop in disbelief once I finish them. When Donovan asks what was wrong, he grabs the laptop and starts reading the stories. When he finishes, he doesn’t look the least bit surprised. He lowers his voice and gulps nervously.

“When I was in middle school, there was this transfer kid who I became close with. His name was Reece,” Donovan explained. “He was bullied in his previous school– that’s why he moved here. He had a tough time connecting with most of the other kids, so I took it upon myself to sit next to him at lunch. Reece was really quiet and never talked in the beginning. But he eventually opened up, and I could see why he was the way he was.”

Donovan told us how Reece liked a girl in his old school, but she was the girlfriend of the class jock, who was the epitome of social success. One day, the jock got into an angry fit and took his anger out on her. Reece stood up for her and told the jock to get lost. In that moment, whatever friends Reece had, quickly abandoned him at the moment he needed them the most.

“Naturally, the jock got his revenge and broke three of Reece’s ribs. Reece also received a flurry of threatening texts from the jock’s crew, telling him to screw off and kill himself. By then, his depression had taken over. He moved here when the harassment was at its peak. Since he entered our school, Reece would appear only some days, and he rarely raised his voice out of fear of being beaten up. I think it was his silence that killed him, not the noose, as he would probably be alive today if he got help.

“I met him too late. By the time he told me all of this, he was planning his suicide, and I didn’t see the signs. I never thought to…” Donovan winces from pain but collects himself, “I never thought to ask what the cut marks on his arms were for, or if he was okay… I just thought I should be that guy that listens instead of the one who talks back, y’know? Yet he told me all of this and I never did anything.”

Donovan hangs his head. Lindsay and I exchange worried glances and try to console him, but we never will get it as Donovan does; we never had a friend who went home one day and never came back.

~

Elijah’s room is dark when we pass by his house. His building is a blessed prewar, a common building in our affluent Brooklyn Heights neighborhood. It’s where lots of townhouses sprung up between the turn of the century and the beginning of World War II. Hicks Street is usually quiet, but not like how it is tonight. Lindsay swears she can hear noises all the way from upper Manhattan.

We approach Elijah’s front porch and ring the doorbell. His mother answers, “Lindsay, Donovan, Ava, what a surprise! Is there anything I can do for you three?”

Donovan steps forward. “We’re just coming to check on Elijah. Is he alright?” he asks, “He hasn’t been answering our texts or calls, and he hasn’t been coming to school recently.”

Ms. Kowalski’s grin disappears like she was anticipating that response, “Yes, well… he has just been a little off since my divorce finalized a month ago, and he’s just wanted space.” She avoids eye contact and starts fidgeting with her hair. “I’ve been forced to drag him out more than once, but he’ll get better soon.” The look in her eyes makes me think she added an “or else” to her explanation.

“Can we see him?” Lindsay questions. Ms. Kowalski doesn’t answer. “I think he might need someone to talk to.”

Ms. Kowalski’s eyebrows raise, “Like a therapist? No, no, no, he doesn’t need any of that ‘therapy.’” She emphasizes that last word with air quotes. “Couples divorce all the time! My own did so when I was ten! I never needed to talk about it. It was just the way it was.”

“But we have reasons! Look!” I protest, pointing to the paper full of the evidence we found out at lunch. She snatches the paper from my hands and scans it. Her expression softens, and her voice lowers.

Ms. Kowalski finishes, throws a quick glance behind her and whispers, “Look, I know I must seem like a fool to say this because I know he needs help, but honestly, I’m just scared that therapy will give Elijah a wimp’s reputation. I’ve never known anyone who has needed therapy, not even in this day in age. I guess it’s something that people my age don’t really talk about.” She gives a pained smile. “You’re welcome to come in if you’d like to discuss more of this.”

We accept her invitation with haste. Elijah’s home is cozy and modern, but Ms. Kowalski insists that we ignore the cumbersome piles of legal papers on the dining room table before she rushes into the kitchen for glasses of water. We make ourselves comfortable on the living room couch while contemplating what Elijah is doing upstairs.

Ms. Kowalski returns with four different glasses, each having a soapy residue to them, indicating that she just washed them. It looks like the divorce has hit her hard too, as she apparently does not have enough time — or maybe the will — to wash dishes. She hands out the glasses, the one she keeps for herself bearing an engraved picture of Elijah when he was about two years old. She clutches it tightly.

“So,” she starts, “have any of you experienced or seen anything like Elijah’s behavior before?”

Donovan places his glass on the coffee table, clearing his throat. “Well, actually, I do have a story about a friend I met a couple of years ago…” and he proceeds to tell the story of Reece.

By the time he’s finished, Ms. Kowalski’s worried face has advanced to shellshock horror. Her hands are covering her mouth, and the glass is out of her reach. I’m glad she put it down before Donovan got to the deep stuff — I’m sure she would have dropped it. Tears start to fall from her eyes. “I can’t imagine what pain he is in,” she sobs. By now, the three of us are comforting her, hugs and all.

“And how awful I have been to him. How blind I’ve…” Slowly, she starts to collect herself. “Thank you, Donovan, for sharing that tragic story.” I look at my watch: it’s only been a half-hour since we’ve arrived, and my entire perspective of this woman has already changed.

Ms. Kowalski wipes her face and blows her nose, “Thank you, all of you. You three have helped me realize more than anything how little I understand the pain my boy is in. I hope you all know that.” We say our goodbyes and exit Elijah’s house. We can still see her on the porch before we turn the corner, wearing a small, sad smile.

~

It seems that our chat with Ms. Kowalski was effective; Elijah is back in school and has started seeing a therapist. He’s started to shed the “giving up” uniform, and he is slowly turning back into his normal self — slowly, though. I still catch him every so often in depressed periods; however, the social worker’s conversation with us about recovering from mental illness taking time has cleared up a lot of confusion for me. I was crushed to hear that some people with depression have it for the rest of their life, but I guess that’s why it’s so important to acknowledge that recovery is a process.

The nice part is that the process’s progress doesn’t just occur when Elijah is talking to his therapist; it can happen just when he’s hanging with us! Since the Elijah we remember has come back, we’ve been able to take day trips to Coney Island and stuff ourselves with Nathan’s hotdogs, while riding the Cyclone about a million times. We’re also getting to know Ms. Kowalski better. She invites us over every Saturday night to hang out with Elijah and watch movies. She often chimes into our activities and tells us interesting stories about the ‘80s edition of Clue we were playing with, or about the engraved Elijah glass she used that memorable night. Turns out, the engravement was based on a photo of Elijah when he was six. Oops.

But, more than anything, I’m just glad that Elijah’s back. His depression is under control, and he is opening up to us more and more every day. I can only hope that those Nathan’s hotdogs are more of a catalyst for happiness and not for weight gain because we’ll be eating those on a regular basis!

Reece’s story is one that I’ll never forget; after Donovan told the story to Elijah, he himself was in tears, and told Donovan how he is endlessly indebted to him. When Donovan asked him why, he said that if Donovan never told his mother the story, she would have never been motivated to get help. And if she never got help, he continued, then he would have eventually killed himself. Reece’s story has impacted our lives so much that we have started taking visits to the cemetery where he is buried to remember him.

I am so happy Elijah is alive.

~

While Elijah’s story of depression ended as a happy one, many do not. According to Health Research Funding.org, 1.8 million teens have had thoughts of suicide during their worst period of depression. Ninety percent of teens who commit suicide had previously been diagnosed with a mental illness. If you, or someone you know, is experiencing suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline (1-800-273-825) for free, confidential support.

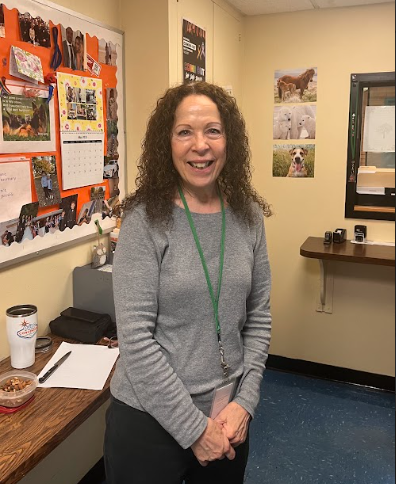

Hey you! Thanks for checking out my profile. I am a member of the Class of 2024 and a storyteller at heart. I love to spend time with my family and friends,...