LHS Students Take a Seat to Make a Stand

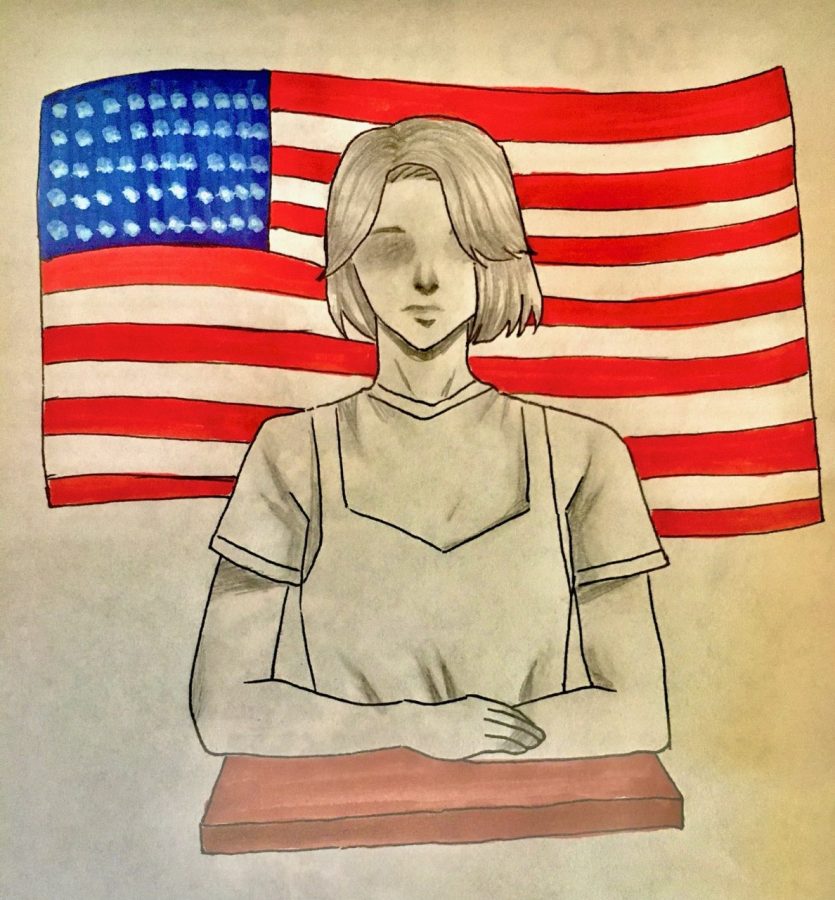

Illustration of a girl sitting in front of the American flag

Colin Kaepernick first sat during the singing of the Star Spangled Banner at an NFL game on Aug. 14, 2016. Kaepernick’s bold move quickly generated rumors and headlines, fueling the debate over whether athletes, and civilians in general, should stand for the national anthem. His symbolic protest has come to be associated with resistance to police brutality, and the topic has become increasingly contentious in years since, as social movements such as Black Lives Matter rise to the forefront of national news. With such divisive presidential candidates and a hostile political climate, “taking a knee” holds more meaning now than perhaps ever before.

AP Government Teacher John Cornicello shared that he has noticed a trend of increased political awareness in his students over the past several years. However, young generations taking to social movements is not a new phenomenon: previous decades, most notably the 1960s and 1970s, beheld eras of young trailblazers who fought for issues such as equality for all races, sexual orientations, genders, and so on.

Years prior, the 1943 Supreme Court case West Virginia v. Barnette declared that compelling public schoolchildren to salute the flag is unconstitutional. It is now, thanks in-part to this ruling and Kaepernick’s spotlight, not uncommon to see students sit during the morning Pledge of Allegiance — LHS students being no exception.

Senior Tess Rechtweg said she chooses to sit during the Pledge because she feels that all people of America are not yet equal: “There is still violence against certain people for the color of their skin or their personal expression, and that needs to be changed,” she explained. “By sitting, I hope to create a change that causes everyone to be looked at as equal.”

Rechtweg said she was hesitant to sit because she was unsure of how her peers and teachers would react. “I was afraid I was going to get in trouble for simply refusing to stand,” she said. Principal Joseph Rainis, also a former AP Government teacher, explained that LHS defends students’ constitutional right to free expression, and teachers cannot stop any student from exercising this privilege.

“I think our school responsibility is to honor the individual and his rights, but also to honor the country and the sacrifice of those who have fought and died on foreign lands,” explained Rainis. “In the moment our troops make that sacrifice, their only connection to our country is the flag they carry.”

Senior Nick McNally began sitting for the Pledge early last school year, prior to the death of George Floyd and the rising popularity of the Black Lives Matter movement. He sits because he feels that equality is not a reality for many Americans and that the Pledge’s promises do not reflect the current state of the nation.

“The Pledge states ‘liberty and justice’ for all, but it’s extremely obvious that there is immense discrimination and racism,” he said. “Truthfully, this nation is not united, and we don’t have liberty and justice for the vast majority of minorities in this country.”

McNally further expressed that he does not endorse the Pledge’s religious undertones. “I believe that making people recite a pledge that is very much aimed at religion — primarily with the mention of God — is not something people should have to recite if they practice other beliefs.” He said the reaction he receives from classmates is mostly neutral: “I don’t get any active hate for it, but I do get a dirty glance now and again.”

Some students sit for a variety of social causes. Junior Max Moscheni said that he does not stand for the Pledge in order to protest against systemic racism, white supremacy, unjust incarceration, homophobia, and restrictions on women’s reproductive rights.

“The nation is supposed to represent freedom and equality for all, so I will sit for the Pledge until the flag and this country truly stand for liberty for all of its people,” Moscheni shared. He added that the reaction from his peers has been neither positive or negative; however, a fellow classmate decided to sit beside him one day during the Pledge, which he said “makes me believe my message is getting across to others.”

On the other hand, some students feel that everyone should stand for the “Star Spangled Banner” and Pledge of Allegiance. Junior Jack Gaertner’s father is a police officer, which he said contributes to his “heightened respect” for America.

“I personally think, being raised by a cop and adjusting to his lifestyle for 16 years, that my respect for my country is definitely a lot higher than it would be if I had a parent that wasn’t registered in law enforcement,” he said. “Standing by this, I will say that in my opinion, the only time a person should be sitting for the Pledge is if they medically or physically can’t stand.”

While Rainis supports students’ choices and rights, he too expressed skepticism for this alley of protest: “I find it ironic that people who sit express their rights in that way; it is because they live here that they’re allowed to sit.”

Rainis added that he hopes to find a more productive way to bring awareness to these social issues, as he feels that sitting for the Pledge may not garner fruitful results. “I’m not sure if homeroom is the appropriate arena for the teacher to broach these topics because it leads down roads that need to be explored. Six minutes between class is not necessarily enough time to have that conversation and gain a mutual understanding of someone else’s viewpoint.”

Despite differing perspectives, LHS students and staff on all sides of the conversation will continue to respect one another’s constitutional right to sit, or stand, during the Pledge of Allegiance.

I am the editor-in-chief of the Horizon newspaper and a member of the Class of 2022. I am also the captain of the LHS Speech, Debate, and Model Congress...