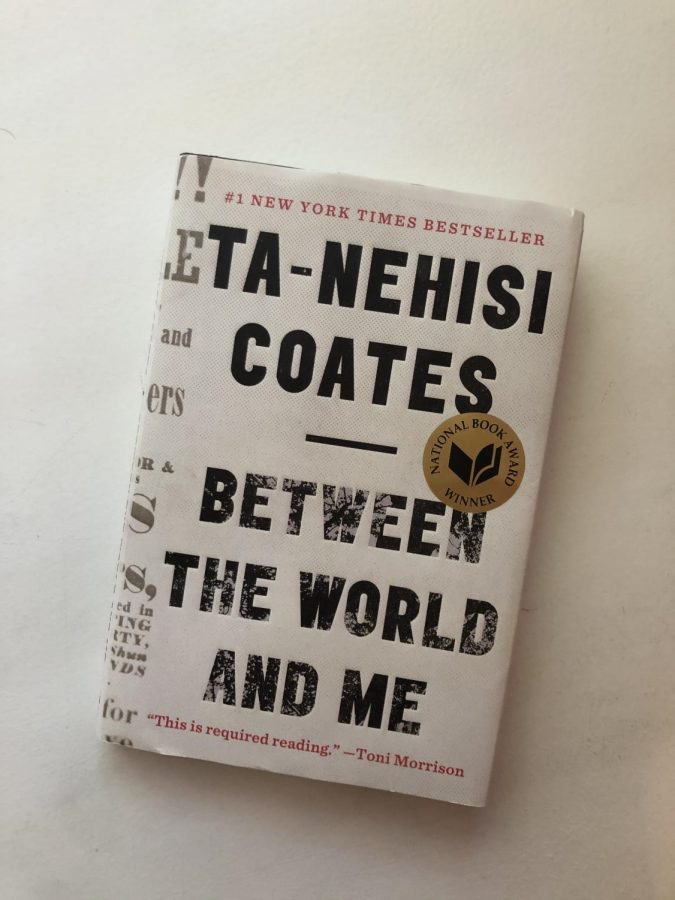

“Between the World and Me”: A Heartbreaking, Inspirational, and Educational Read

America, the land of the free and the home of the brave! This concept of our boundless equality, undeniable freedom, and government of justice is reinforced in our minds at every available opportunity: in a classroom, at a baseball game, on the late-night news channels. Yet, there is a clear disconnect between the mantra of our nation and the preachings of a man whose brother was viciously murdered by an officer sworn to protect him.

Today’s “woke” new buzzword is anti-racism; anti-racism includes actions, movements, and policies developed to oppose racism, rather than simply being “not racist.” The goal is no longer to end injustice on an individual level alone. We are now tackling the systemic racism that exists rampantly within government and society. I do not pretend to understand what it means to be black in America. But, I vow to educate myself, to shed any ounce of preconception, biased opinion, and implicit privilege that has become a long-overused scapegoat.

The power of writing is often conjured during times of conflict, times of uncertainty, and periods of hardship. Some of history’s most influential works have been the offspring of discomfort, and their authors’ teachings continue to inspire in spite of time’s boundaries. I have read novels about slavery and racism of generations past. I read those stories with disgust for people’s malevolence and an appreciation for how far society has evolved to accept people of all colors; I had not yet begun to grasp that racism is not some foreign, ancient, faraway hatred that has been magically cured. It is an ongoing epidemic, a mammoth violation of human decency that is very much so present today.

In Between the World and Me, written as a letter to his son, renowned journalist and author Ta-Nehisi Coates tells his own story of racial injustice, and imparts his wisdom as a black man from a Baltimore hood. I learned an immense deal from Coates’ insight, the type of education not afforded to me in a classroom where racism “ended” with the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

Coates uses certain motifs throughout the book to describe an overarching injustice. He often refers to “the Dream,” a phrase to represent the vast possibilities and opportunities for people who “think they are white,” as well as the outward denial of racism in the present day. People who think they are white, known as “the Dreamers” to Coates, rely on forgetting and denying America’s past tragedies and crimes in order to diminish their sense of guilt for the actions of their ancestors.

Notice the use of the word “think” in reference to the “the Dreamers.” Coates believes that race is a social construct. For centuries, people have been grouped in social classes based on their skin color, ignorant of the culture and background of the group themselves. “White” and “black” diminish the importance of an ethnic group’s traditions, values, and heritage, and creates a division between people with different skin colors. As Coates explains in the novel, “Race is the child of racism, not the father. And the process of naming ‘the people’ has never been a matter of genealogy and physiognomy so much as one of hierarchy.”

Another powerful theme of Coates’ novel is the abiding sense of fear. Growing up in a poor neighborhood, gang violence was prevalent and practically inescapable. The only way to stay out of trouble was to monitor every movement and every word: “…each day, fully one-third of my brain was concerned with who I was walking to school with, our precise number, the manner of our walk, the number of times I smiled, who or what I smiled at, who offered a pound, and who did not — all of which is to say that I practiced the culture of the streets, a culture concerned chiefly with securing the body…”

He was taught from a young age that the only way out of the cycle of violence was to succeed in school. Sixty percent of black men who drop out of high school will end up in jail. Thus, failing at school became a justification for violence in the streets. How could Coates value his education when he so desperately had greater things to worry about? With one wrong look, a gun could be aimed at his head and algebra class would not be able to save him. He resented the schools because instead of providing a solace as they should have, they merely enforced discipline rather than appreciation for learning. “If the streets shackled my right leg, the schools shackled my left… I suffered at the hands of both, but I resent the schools more.”

The reader continues to learn of Coates’ fear as an adult, even after graduating college, moving to New York City, and having a son with his wife. The fear takes on a more sophisticated form, no longer the personal fear of self-preservation but the fear for his child whose body is in the hands of “the Dreamers.”

This novel is, to say the least, an eye-opener of the greater injustice that exists in our country. I no longer see racism as a personal offence of violence but as an institutionalized system that is largely ignored. Between the World and Me is wildly heartbreaking, inspirational, and educational. I urge you to read it to take the first step in becoming an anti-racist; educate yourself, and peek behind the veil of “the Dream” that fogs our vision and leaves us a shallow puddle of ignorance and denial.

I am the editor-in-chief of the Horizon newspaper and a member of the Class of 2022. I am also the captain of the LHS Speech, Debate, and Model Congress...