This Is Not How the ACT Should Act

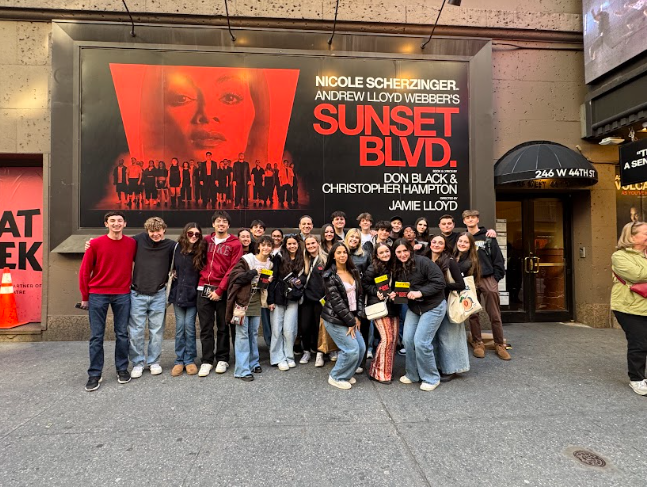

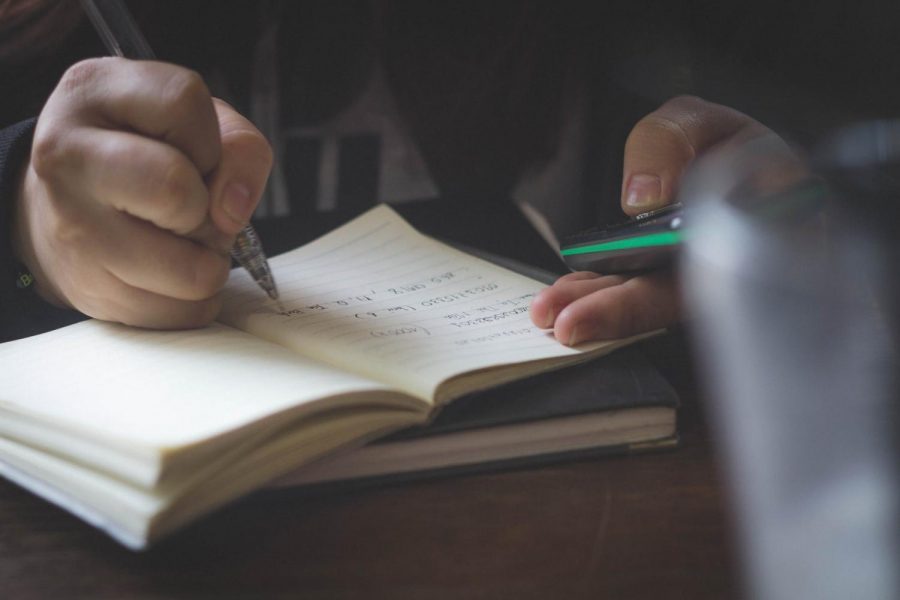

Standardized testing rose in popularity in the mid-1900s to allow colleges to compare applicants on a national level. Since then, tests such as the ACT and SAT have exploded in popularity, and taking at least one of these exams is required to earn admission into most universities. And, if an applicant desires to attend a prestigious university, he/she will not just have to take the exam but score well on it, too. Senior Arpie Bakhshian stated, “Getting into a college is so hard nowadays that having a high-test score has become more of a requirement than an exception.”

One of the hardest parts of the exams is simply the length of it. “I always struggle with just sitting for the test. It takes up so much energy. By the time I get to the science section [on the ACT], I can hardly focus,” said senior Casey Shea. To combat this issue, the ACT announced that for the September 2020 test and beyond, students may retake specific sections of the exam after sitting down for a full test once. While many will praise this new policy as it allows students to remain alert for the entirety of the exam and specialize in specific sections, this new policy may place more of a burden on students than they realize as universities may begin to devalue higher test marks and score disparities among class divides will increase. In fact, the new ACT policy will actually be harmful for future applicants.

Since many universities allow students to “super score” their ACT mark —that is combine the best scores of each section that students receive on different testing days— allowing students to take specific sections on different days eliminates part of the difficulty of the exam. Students can now focus on just one section to study without having worrying about performing well on other sections. While this may seem ideal to students, if the exam becomes easier, scores will increase, which makes admission into universities even more competitive. Senior Lia Cohen stated, “If everyone takes individual sections, then they can focus all their time to perfect that section before the test and have a higher super score. I always struggled with maintaining high scores in the sections I already did well on when retaking the test because I would try to just study for my lower sections, but then my previously high sections would fall.” If everyone starts to do exceptionally well on the ACT, then the test is not performing its function of quantitatively comparing applicants. As Bakhshian explained, “It will be a lot easier to get a 36.”

While students’ scores may increase, this may not even impress colleges despite the hard work students dedicate towards achieving a high mark. Test scores may hardly factor into an applicant’s admission chance if everyone receives similar scores; only, it will become a reason not to admit a student if he/she does not receive a mark comparable to other applicants. Even just a point difference on the exam may make a difference in one’s admission chances. Thus, colleges will be forced to place a larger emphasis on personal essays, extra curricular activities, and recommendation letters. For applicants, this can be daunting since they will have less control over their admission chances since qualitative factors, like one’s essay, are much more subjective compared to numerical test scores. Cohen stated, “Admissions will become more of a crapshoot. If everyone gets above a 30, how is that impressive and what’s the point of the ACT then?” Considering the influence of grade inflation on high school students’ grades, applicants who attend more academically challenging schools may rely on standardized testing to prove to colleges his/her academic ability. The ACT’s new policy can threaten these students’ chances of admission and dilutes the ultimate purpose of the test: to compare students’ academic abilities from vastly different backgrounds.

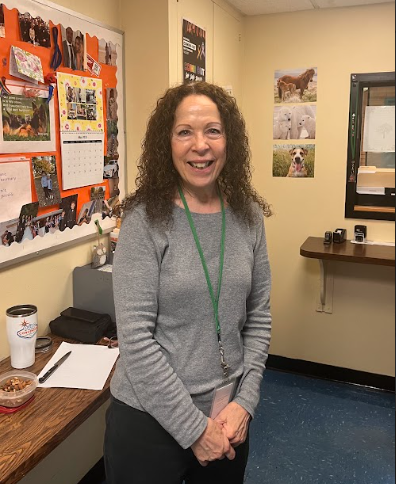

Moreover, standardized testing, including the ACT, has historically favored students who can afford to pay for a prep course or a private tutor. Some lower-income families come from homes where English is a second language, which might make the English and reading sections considerably harder for that child. To shine light on this phenomenon, the SAT announced last year that it would be introducing an adversity score to give context to colleges on the type of community students grew up in and potentially mitigate the influence of wealth on students’ admission. The ACT seems to be moving in the opposite direction of lessening the role of money on a student’s score as this new policy seems to exclusively help higher-income families. Students from lower-income households may not have the resources to “perfect” specific sections before taking part of an exam. Moreover, several students may not even be able to afford to take the exam multiple times, making them ineligible from benefiting from this policy. Ultimately, this new policy will be harmful towards lower-income applicants and is quite unfair. It is a threat towards diversifying universities and only seems to favor people with enough money to take the test multiple times.

Since, generally, most students’ scores will increase and lower-income students will struggle to keep up with their wealthier counterparts without the luxury of a prep course, in an ironic turn of events, many schools may become “test optional.” Countless universities have become test optional within the past decade to combat the influence of wealth on standardized test scores. Ultimately, a policy that the ACT enacted to draw students to take their test over the SAT, may instead drive several colleges away from even requiring standardized testing at all.