The Story of Holocaust Survivor Irving Roth

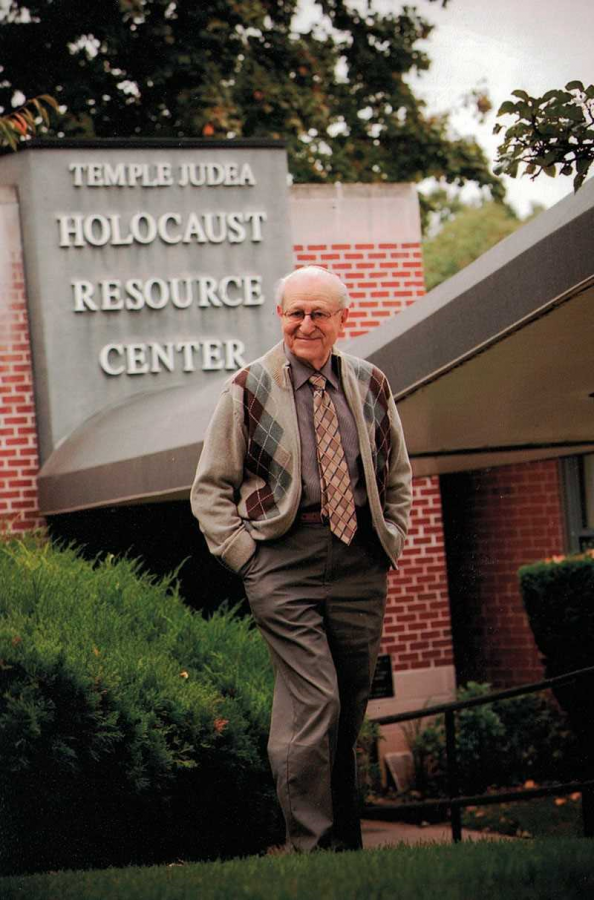

From a young age, I have read novels depicting the horrors of the Holocaust, and yet I continue to contemplate this time. My uncle, Todd Chizner, is a rabbi at Temple Judea in Manhasset, New York, so I recently reached out to him with a proposition: Would it be possible for me to interview a Holocaust survivor from his congregation? Unbeknownst to me, his synagogue has an entire group of survivors and a research center dedicated to educating people about the Holocaust. This was my opportunity to finally get an interview with a Holocaust survivor.

Now more than ever, there is such an immense responsibility to educate ourselves and others about the atrocities of the Holocaust. Sadly, with each year that goes by, many survivors are dying due to old age. There is such precious time to get authentic firsthand accounts like the interview I was privileged to experience. And, as anti-Semitism continues to rise and mass genocides are still occurring to this day, we must look upon the mistakes of history to ensure that the future holds no more Holocausts.

I had the honor of meeting with a gentleman named Irving Roth. Mr. Roth, now 90 years young, has devoted his life to not only teaching people about his experience, but to honoring the 6.5 million who perished in the Holocaust. In the two hours that I sat down with Mr. Roth, he told me about his life from beginning to present. Here is his incredible story:

Roth was born on September 2, 1929, in Kosice, Czechoslovakia. He grew up in a city called Humenne, which he described as “modern” and “small” with a population of about 7,000 people, one-third of which were Jewish. Roth lived a typical life up until the age of nine. He went to public school, played soccer, went ice skating, and swam at the beach. He attended Hebrew school six days a week and did his homework with “the prettiest girl in school.”

In 1938, Roth began to notice some changes in his city. When Germany took over the western region of Czechoslovakia, he was told to chant the German national anthem in school every morning. In the summer of 1939, signs were hung up on the park: “NO JEWS, NO DOGS.” Slowly but surely, his typical life turned into the nightmare we now know as The Holocaust.

As the rules and restrictions on Jewish life became more severe, Roth’s parents applied to come to America, as many Jews living in Europe did at this time. However, due to America’s quota system, the Roth family would have to wait five or six years to gain entry into the country. Thus, they had no choice but to stay in Slovakia and wait until the war ended and life could return to normal. They had no idea what was in store for them.

As summer faded to winter and winter to spring, Roth was no longer allowed to attend school with the other kids. In fact, it became illegal for any Jewish student to attend the public school, and every Jewish teacher and faculty member was fired. The Jewish parents rented the Hebrew schools and held classes for their children in the mornings before work. But eventually, there was no longer work to attend. In September of 1940, the Nazis made it illegal for any Jew to own a business. Irving’s father was an accountant and owned a lumber business. Because he was prohibited from owning his business, Roth’s father was forced to hand over his life’s work to another man. Then, there was a curfew instilled for Jews.

By 1940, ghettos were being built all around Europe, although not in Slovakia at the time. Rumors buzzed around Humenne of Nazi death camps in the Soviet Union, Jews being forced out of their homes, and marched to their deaths. However, many like the Roths refused to believe such unfathomable stories, or “propaganda.” Roth’s father was a soldier in the Austria-Hungary army in WWI: a Jew fighting alongside Germans. Now, only 20 years passed and his former allies became his greatest enemies. “Their objective was very clear: to get rid of all of the Jews of Europe.” After six months, almost 500,000 Jews were murdered in the Soviet Union. But the Nazis were not satisfied with the numbers.

On January 20, 1942, a group of Germany’s leading intellectuals, one-third of the men holding Phd’s, held a conference to discuss how to more effectively and inexpensively exterminate the 11 million Jews in Europe. Their solution was to create death camps and murder the Jews using toxic gas and burning the bodies in a crematorium. This has gone down in history as Hitler’s Final Solution.

And so death camps grew like wildfire in Poland, while Slovakia payed Germany a generous sum to take the Jews off of their hands. On a Friday night in the summer of 1942, there was a knock on almost every Jewish home in Humenne. The families were given all but ten minutes to pack a suitcase, and they were pushed out of their homes. The Nazis forced the 1,800 Jews into their synagogue (which only fit about 400), locked the doors, and did not open them for two days: no food, no water, no bathroom. On this night, the Jew’s place of worship became their prison. Come Sunday afternoon, the Nazis opened the doors and loaded each and every last man, woman, and child standing into cattle cars. They were never heard from again.

Fortunately, the Roth family was of the few Jews who remained in Humenne due to the father’s work exemption. However, the Jewish school which was once filled with hundreds of eager Jewish pupils and many teachers, now only had 11 students and one teacher. Then, one morning in 1943 as Irving and his grandparents were leaving synagogue, his grandfather was arrested. After a long effort of contacting and paying off many people, Irving’s family finally got his grandfather out of jail. “We know we’re in trouble. So now we have to do something. So what do you do? Well, we decided that we have to disappear.”

At this time, Hungary, which is located directly next to Slovakia, was sending their Jewish men to fight in their military, rather than to death camps. Because of this, Hungary was the safest place for a Jewish family to live. So, the Roth family legally crossed the border into Hungary and moved into a small village. Once they got there, Roth’s parents realized that they needed work in order to support their family. They traveled to Budapest for his father to find a job and to wait for the war to end.

By the spring of 1944, when Irving was 14, Germany decided it was time to get rid of Hungary’s Jews. Suddenly, what was intended to be a safe haven for the Roths became just another Nazi nightmare. Ghettos were built all over and Jews were sent to death camps. One day, the Roths were brought to a ghetto where they lived under a roof with no walls. Days later, Roth and his family were locked in a cattle car. They drove for three days straight using a bucket for a bathroom and the holes in the car for a window.

The night that the cattle car finally stopped, Roth, his family, and about 5,000 others jumped off the cattle cars to be greeted by angry Nazi soldiers. As guards yelled at them to leave all of their possessions on the train, Irving looked around and saw smoke coming out of chimneys. “My cousin is standing next to me and he says to me, ‘Irv, what kind of factories do you think these are?’ I tell him, ‘They’re gonna make soap out of us. But if I become a bar of soap, I’ll refuse to bubble.’”

Suddenly, families were being separated as two lines were formed: one with Roth’s grandfather, grandmother, aunt, and 10 year old cousin; the other with Roth, his brother, his cousin and other men from ages 15-30. The latter was marched from the train to another part of the camp and were told to go inside the barracks. Here, the only thing inside these barracks were “shelves” to serve as beds. The next morning when Roth awoke to loud whistles and yells, he was served something that “tasted almost not quite like coffee for breakfast.” One by one, the men were called by name to a small table to get numbers tattooed onto their arms. And just like that, they were no longer people: the Nazis had made them objects, numbers.

Then, once again, the trail of smoke lingered over Roth’s head. “We asked another prisoner in the blue and white stripe uniform, ‘What happened to our relatives?’ He points to the chimneys and he says, ‘See that? That’s where they are. They were murdered and then they were burned.’” Irving and his brother could not believe, or even fathom, what they were told. They thought it was just another thing to scare them. “In reality, that’s what happened. That night, 5,000 people arrived and 4,700 of them became ashes.”

Later, Roth and his brother were assigned their work duty. At first, they were placed to work in a gravel pit. Eventually, their job was to plow the fields and care for the horses, from early morning to late at night. Because of the extremely meager food supply at Auschwitz, the meals only supplied about 300-400 calories a day (“consisting of black liquid in the morning, some form of soup at noon, and a piece of bread”), barely enough to keep someone alive. Fortunately, Irving discovered a way to supplement his diet: he would cook and eat the sugar beets which were meant to feed the horses. “You take two sugar beets, give it to the blacksmith, he keeps one, and roasts both of them…That’s not called stealing. That’s called organizing…The objective was to stay alive.”

While Roth and his brother struggled to survive in Auschwitz, WWII continued on. Hopeful news of Hitler’s weakening army spread around the camp as Germany was bombed day and night. But on the morning of January 18, 1945, things were different. On this morning, rather than being marched to the horse stables to plow the fields, Roth and the other prisoners were marched out of Auschwitz. For three days, thousands of emaciated prisoners were forced to march through the unforgiving winter of Poland. Then, they were put on open train cars and after many hours, arrived at dusk to an open field; they were at Buchenwald.

The prisoners marched on as commanded and were told to undress: they were to take a shower. This was for most their first shower in months, maybe years. Next, they were told to go through a set of doors, many expecting to be handed clothing. But when they reached the end of the hallway, they realized there was no way out.

“I turned to my brother and said, ‘We’re in a gas chamber. What do we do?’ He said to me, ‘If it’s the end, you say the Sh’ma and that’s it.’… I cannot tell you whether it was ten minutes or a half hour. As we are standing there, suddenly a wall is opened up and we see sunshine coming in.” Astoundingly, what they thought to be a gas chamber was merely a tunnel from the shower to the outdoors. They were then taken to a warehouse to get clothes, and later to their barracks. Buchenwald, a concentration camp originally built to hold 5,000 now had over 50,000 prisoners. “If you get a boiled potato every second day, you’re lucky.”

One day when they were standing in formation, the Nazis began to separate the young from the old, much like when Roth first arrived at Auschwitz and was separated from his grandparents. This time, he was separated from his brother. “I tell my brother, ‘Maybe you should come to my side.’ He says, ‘Do I know which is right? Where the probability of survival is greater? It is all in God’s hands.’”

And so Roth’s group, about 300 kids aged 14-16, and one eight year old, were taken to Block 66 at the end of a hill. Roth’s brother and the others with him were shipped out to another camp called Bergen-Belsen. “That’s all I know. And I am left there.”

By the beginning of April, death marches began again. Roth knew what was written in his future and had felt in his heart that he would not survive. On April 10, Roth and some other kids from his Block sought asylum under a building, but their hideout could not be masked; a guard and his dog found them. “They gathered 10,000 of us, the last of the Jews in Buchenwald. The guards come along, we are ready to be marched out, and while we are standing there, a siren goes off.”

American airplanes flew overhead and bombs came crashing down, all but one city over. Terror fell over the Nazi guards’ faces and air raid sirens blared for hours on end. Eventually, the prisoners were told to return to their barracks. Another day alive. By 11 o’clock the next morning, every Nazi guard was gone. Roth’s kapo told everyone to stay down, for their was still open fire and bullets whizzed through the air. “At 3 o’clock in the afternoon, two American soldiers walked into my barrack. I thought Wow, the messiah just came. Nobody wants to kill me? I’m alive? Hungry, though!… Imagine you see about 300 kids, none over 75 pounds, skeletons shuffling along. Both soldiers broke down into tears.”

By the next morning, more American soldiers arrived at the camp along with doctors, medics, and lots of food. Days later, the American commander led the kids past the gate and out of the camp where they were disinfected and given clothes to wear. But what clothes were available in a German warehouse in the midst of WWII? None other than German army uniforms.

“We were taken to a building and we’re assigned four kids to each room. Each room has four beds in it, and four mattresses, and the whole thing. It’s The Plaza! And we get fed three times a day, and we get chocolate bars every so often, and each one of us gets a carton of Camel cigarettes a day. Imagine four boys, 15 years old, each one with a carton of Camel cigarettes and no supervision…But I traded my cigarettes for chocolate.”

With each day that passed, Roth slowly regained his strength. But quickly, the harshness of reality and questions of the future came crashing down upon him. What should I do now? Where should I go? Roth walked through the camp, hoping to find someone who knew where his parents could possibly be. As he walked into one of the buildings, he saw someone he recognized. “He turned to me and he says, ‘You’re Irving Roth, right?’ I said, ‘Yea, I know you.’ He was a kid from my town. He tells me someone else from my town is here. Now three people from my town survived!…And now I am a person. I was addressed by my name.”

And so the three boys travelled back to their city to look for their families. Roth asked around the town if anyone had heard from his parents. When he heard rumors of his parents’ survival, he immediately took a train back to his old village. “I open up the door and there’s my mother in the kitchen. I say, ‘Hi, Mom.’’’

As Roth and his mother reunited, she told him of her plight to survive the war. Because they were in Budapest at the time, Roth’s mother and father were of the last group of Jews to be shipped to concentration camps. Just as Budapest began collecting the Jews, Roth’s father grew severely ill with typhus and fell into a coma. An ambulance came and brought him to a non-Jewish hospital because he was extremely contagious. For many days and many nights, a Christian nurse took care of him and eventually, he woke from his coma.

With no where to go, Roth’s parents began to panic; it was the height of Hitler’s power and almost every Jew in Europe was shipped to a concentration camp. By a stroke of luck, the nurse who cared for Roth’s father agreed to let them hide in her one bedroom apartment where she lived with her daughter and granddaughter. But her son in law was not home: he was off fighting in the Hungarian-Nazi army.

One day while struggling to hide in the minute apartment, the nurse’s son in law came home from the war. The Nazi’s wife tried to convince her husband that Irving’s parents were distant relatives staying with them during the war. She pleaded with and bribed him to stay quiet about the two “relatives” living with them. And so for months, Roth’s parents lived in a Nazi’s apartment and survived the Holocaust.

In February of 1945, the Russian army invaded and liberated Budapest. They assumed that every male still living there was a Nazi and began shipping these men to Siberia, presumably to a POW camp. “They walk into this apartment and see my father. They said to him, ‘Get dressed you are coming with us.’ My father tells these Russian soldiers, ‘You don’t want to take me, I have typhus.’” So the Russian soldiers sent a doctor to the apartment to see if Irving’s father truly had typhus or if he was lying. “The doctor examines my father and says, ‘Yes, you did have typhus but you no longer have it.’ My father says, ‘That’s right.’ The doctor says to my father, ‘You are a Jew?’ My father says, ‘Yes.’ He says, ‘Me too.’”

Knowing that Roth’s father was healthy yet Jewish and in danger of being deported, the doctor quarantined the apartment, forbidding Russian soldiers from entering. “So my parents survived because someone was willing to help.” From there, the family returned back to their home town. “So what do you do now? Our neighbors didn’t want us back. Just because the law was removed doesn’t mean that anti-Semitism was removed.”

Immediately, Roth and his parents reapplied to come to America. On February 11, 1947, they arrived in New York and got an apartment in Brooklyn. Knowing absolutely no English, Roth went to night school and got a job. In September, Roth turned 18 and entered high school as a freshman. He took classes and became captain of the soccer team, slowly integrating himself into the Brooklyn environment. After only three semesters of school and passing all of his regents exams, Roth graduated high school. “That was the most fun I ever had in my life.”

After high school, Roth got a job and finally began rebuilding a normal life. But in 1950, he was drafted into the Korean War. For two years, he went to radio-communication school and became an instructor in radio-communication for the U.S. army at Fort Knocks, Kentucky. Once discharged from the army, Roth went on to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees in engineering at Polytechnic University in New York City. “I got a job, got married, had children…and here I am, 70 years later, talking to you.”

As I left the synagogue where I met with Mr. Roth, thoughts swirled around my head: I was dumbfounded. How could a person possibly live through such trauma and become the successful man he is today? “I was 15 years old. I wanted to live. And I thought maybe someday I would be able to tell this story to somebody, about this crazy world that legal governments put together.” I am still so amazed by Mr. Roth’s story and I feel so grateful to have met him. Never forget. I never will.

For Irving Roth’s full story, please read his book Bondi’s Brother.

I am the editor-in-chief of the Horizon newspaper and a member of the Class of 2022. I am also the captain of the LHS Speech, Debate, and Model Congress...