Too Much! Too Little! Just Right: The Story of LHS’s Regents Weighting Policy

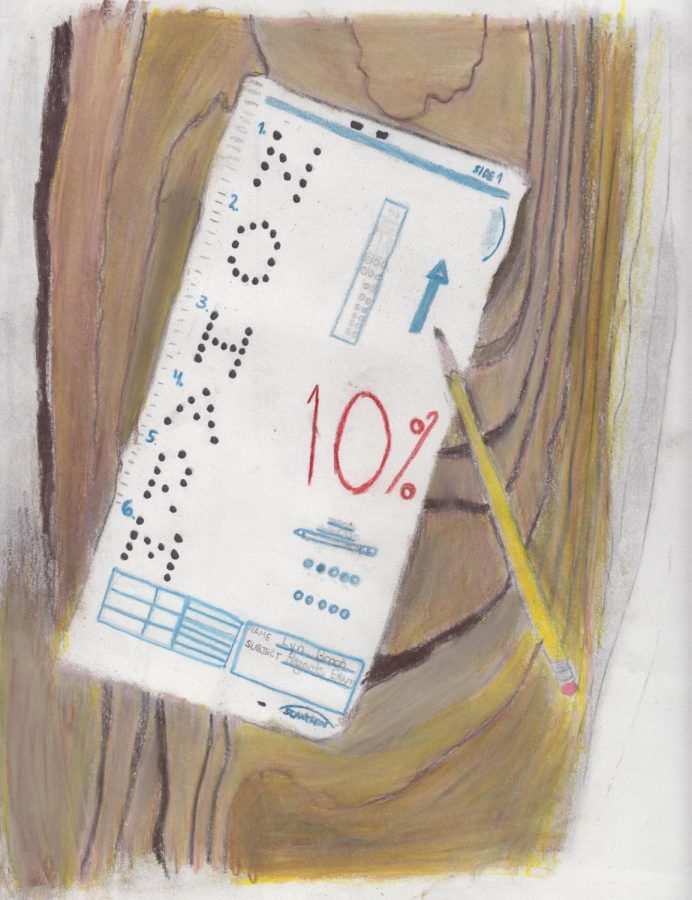

After several policy vacillations and a months-long discussion between building administration, the Board of Education, teachers, parents, and students, Principal Rainis announced on Sep. 17 that Regents exams will now and for the foreseeable future count as 10% of a student’s course grade.

For a long time, the New York State Regents, like any other final exam at LHS was counted as 20% of a student’s final grade for the class, alongside the four school marking periods. However, under tremendous pressure from parents claiming the Regents are becoming increasingly difficult and unfair, the school administration, in conjunction with the Board of Education, decided on changing the weighting to the “Do No Harm” Policy, wherein Regents grades count only if they help a student’s GPA, and are exempt if they hurt it. However, the policy was met with sharp opposition, and it was eventually redacted and replaced with a compromise of 10% weight.

The push to create a new Regents weighting policy that led to the Do No Harm decision was initiated by a series of flawed Regents exams on which many students scored poorly. The state admitted that mistakes were made, and unfair questions were included in some of its Regents exams, most prominently Geometry, Chemistry, and Algebra II. However, the Regents’ bad year seemed only the straw that broke an old, unpopular camel’s back.

As Principal Joe Rainis explains, “The impetus for the change was really an outgrowth of the rebellion against the battery of grades 3-8 testing that students endure [i.e. the NY State Math and ELA exams]. Large numbers of people agreed that those tests served no purpose and opted their students out. When the state made a few mistakes in implementing the common core in the Regents exams, it fueled the fire already burning against the inconsistent-at-best state exams.”

The Do No Harm movement was led largely by parents who believed that the policy would protect their children against these exams. Debates on the Lynbrook Parents Facebook group help elucidate those parents’ perspectives. For example, Amy Curley wrote, “The no harm practice was put in to place to protect our kids from the flaws of state tests to stay competitive with neighboring districts with regards to grade point averages.” Another argument mentioned that bolstered the Do No Harm decision was the policy’s impact on special needs students. As explained by Moira La Barbera, “The greatest beneficiaries of this policy are our special needs students who are passing the curriculum and classwork but struggle with the state created, poorly drafted, error prone Regents exams. This policy could be the difference between getting a high school diploma which gives them a pathway to a post secondary education or leaving them with a certificate that does not provide the necessary college prerequisite.”

While vocal parents were able to mobilize the BOE and administration on the policy change last year, the decision received backlash at the June BOE meeting, where angry, yet civil dissenters were hard at work. The Lynbrook Teachers Association attended the meeting sporting its bright red “Keep Calm, and Teach On” t-shirts. For nearly an hour, the public forum was addressed by these teachers, in addition to students, parents, and guidance counselors who argued that the Do No Harm Policy threatens the integrity of LHS teachers and the school as a whole by unnecessarily inflating students’ grades. Craig Kirchenberg, English teacher and president of the teachers’ union, explained how the policy created an “uneven playing field.” He further lamented the policy’s execution: Lynbrook teachers who were allegedly promised that they would not have to conduct the grade adjustments themselves, were in fact required to hand-calculate whether the Regents grade would count or not, which was especially galvanizing to those who already disapproved of the policy.

Notably, English Teacher Carla Gentile, who says she normally does not attend BOE meetings, felt compelled to speak, imploring, “One of the things I’m really having a hard time with is that I’m being directed to do something that goes against every single thing I know about good pedagogy. I am, and we are, sending a message to our kids to game a system when a system isn’t working for us.” She further elaborated in a private interview, “Our first priority in Lynbrook should be to give our kids the very best advantage they can possibly have. I truly believe that having a nebulous system that has no transparency for the colleges to evaluate transcripts will eventually earn us a bad reputation: We will be viewed as a school that games the system. That doesn’t help our kids. It hurts them.”

As Gentile mentioned, the Do No Harm Policy has serious implications for college admissions. In fact, the Lynbrook Guidance Department, headed by Laurie Mitchell, spoke at the meeting to explain what their college admissions contacts thought of the policy. After speaking with representatives from Syracuse, Binghamton, Hofstra, and many other colleges that accept a large number of Lynbrook graduates each year, Mitchell explained, “Having a standard for one student and another for others calls into question how our grades accurately portray students’ academic performance and ability. Our teachers certify the grades and put their reputation and teaching license on the line. Guidance counselors certify the efficacy of transcripts and put the reputation of Lynbrook High School on the line.”

Rainis adds, “[College representatives] didn’t think it was a sound practice, and many schools do look at Regents exam scores in various ways. For example, Syracuse thought that having an inconsistent means for establishing GPAs raises questions.” Students attending the meeting were not happy to hear this news, but many also disagreed with the policy beyond the direct effects it might have on their college applications.

Senior Kaylie Hausknecht says, “I watched all of last year as some of my more extrinsically motivated peers put minimal effort into making sure they had a deep and long-lasting comprehension of their courses’ curriculums. Regents examinations are not only important for evaluating mastery in a subject, but they are also important for providing that little bit of motivation that some students need to force them to work hard throughout the entire year. The sentiment that students do not need to be held accountable for all the information they learn in a class is not one that I think should be seen in the halls of LHS, and unfortunately, I think the DNH policy helps to cultivate that mindset.”

While parents began the movement that led to the Do No Harm Policy, many also contributed to its repeal. One such parent, Eileen Linzer, wrote a letter to the BOE explaining her stance: “The very concept of making the score of a final examination optional – Regents or other – is seriously detrimental to the character of the type of student I hope we are trying to mold…I do not want my children to be effectively told that they do not need to be accountable for a poor performance. That is, quite literally, the exact opposite of what we try to teach them at home and what I fully expect the schools to be teaching them as well.”

Thus, with disapproval of the policy coming from all corners of the school community, a committee was created to diligently analyze all the different proposals for the Regents weighting over the summer and come to a more informed decision for the 2018-2019 school year. At the September BOE meeting, the decision of this committee was presented: All regents and finals will count for 10% of the course grade regardless of what the student earns on it.

Rainis explains, “The committee was myself, the superintendent, and LTA leadership. It was an effort to look at what we discovered over the course of last year regarding the way college admissions officials seemed to be interpreting what we were saying about the Do No Harm Policy. We had to make a decision about what can we do that continues to protect those who don’t do as well on standardized tests, but that provides consistency. The two ends of the spectrum are 20%, which was the policy for many, many years, and 0%, which might prevent students from taking the exams seriously. 10% was the middle ground between 0% and 20%. Class work, which used to count 80%, now counts 90%, which helps students who don’t do well on standardized tests significantly. However, it still keeps everyone focused and working until the end of the year because that end exam does count for something, albeit 10% of that child’s grade. We felt it was a fair middle ground.” Gentile agrees, “At least now that exams count as 10%, a college is aware when they evaluate a transcript of how grades were calculated. There is integrity to having consistency.”

However, even after a lengthy presentation by Rainis and Mitchell, a few parents at the September BOE meeting still did not see it that way, speaking in the public forum to claim the committee was negligent with regard to the special education population at LHS by not including a special education specific faculty member on the committee. District administration responded by assuring the public that the statistics used to make the decision actually did specifically consider the policy’s effects on special education students. The remainder of the comments at the meeting conveyed sometimes begrudging, but mostly whole-hearted support of the 10% compromise, a happy ending to a papa bear of a controversy.

I began participating in Horizon as a writer in my freshman year, and I was editor for A&E as a sophomore. As editor-in-chief of the website my junior...