Cramped in a small New York City theater on a tepid afternoon during spring break, I sat down to watch renowned German director Wim Wender’s first Japanese film: Perfect Days. Perfect Days was released in November of 2023 in Germany, but the film has just recently garnered popularity in the United States. Playing primarily in small urban theaters (the kind where you expect theatergoers to have berets and black turtlenecks), Perfect Days is a diamond in the rough, a film that one must search for to uncover.

As I sat down in the theater, surrounded by elderly people who would probably fall asleep within fifteen minutes of the film (a testament to their age rather than the film’s substance), I watched the lights dim, and the screen change to reveal the beginnings of a film I did not know I would be thinking about for many weeks to come.

Set in Tokyo, Perfect Days follows the story of Hirayama (played by Koji Yakusho), a toilet cleaner in his late 60s. Hirayama lives the same day, every day. He wakes up, goes about his morning routine (which includes watering his many plants), and then drives to work in his modest Japanese truck, where he cleans toilets around the city. While Hirayama drives to work, he is accompanied by the songs in his impressive tape collection. Every day Hirayama drives to work, he selects a different song, though his choices are primarily composed of American music. This is one of the very few facets we can attribute to Hirayama’s personality, to his tastes that go beyond the composition of his simplistic normal routine. The film follows Hirayama through his linear existence, where he rarely deviates from his regular routine, and when he does, he and his activities always find a way back to their regularity.

For a while, everything stays the same. We watch Hirayama begin his morning routine in his modest apartment, go to work, and take his dinner at various restaurants in Tokyo. Hirayama’s personage is that of a regular person. And yet, during the film, I was never bored, because the life of Hirayama, I realized, truly was unremarkably remarkable. The few interactions that Hirayama has with others make this routine so fascinating. A visit to the bookstore is an opportunity to observe Hirayama’s interaction with the bookseller; a visit to the neighborhood sushi restaurant reveals a tense relationship with the bartender; and a lunch break in the park allows us to notice another woman, sitting close to Hirayama, who seems to lead a similarly unremarkably remarkable life. This is the beauty of our observance; in this film, the viewer is given the opportunity to observe, something that many of us do not regularly practice – we are always acting and never watching. But Hirayama is the greatest teacher, for, as a character, he is an observer, too. Hirayama is a stoic and reserved man, and most of the interactions displayed in this film are ones in which he is merely a bystander. Yet, Hirayama is able to perceive the beauty of that which is ordinary, and he shows the viewer this, too.

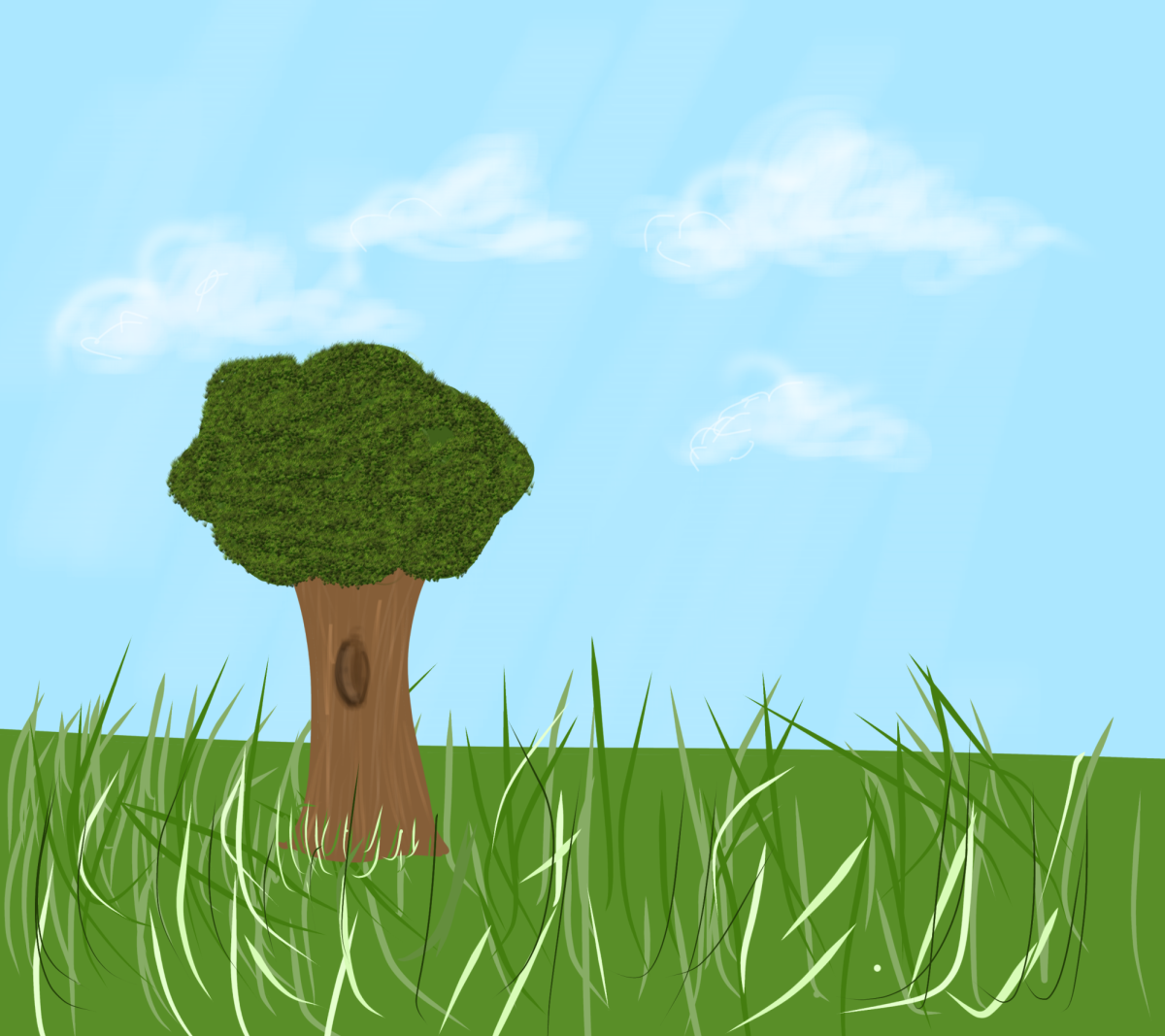

The word ‘komorebi’ in Japanese means “sunlight leaking through the trees,” and it was the original title for the film before it was changed during its translation to English. What this word represents is the importance of paying attention to ordinary things, for they have just as much beauty as life’s abnormalities. When Hirayama takes his lunch in a shady park every day, he looks up at the trees, watching light come through them. Then, he takes out his portable camera, points it up at the sky, and takes a photo. We watch Hirayama do this every day, and it is a testament to ‘komorebi’–it is Wenders trying to show the viewer that there truly is beauty in everyday things–we just have to look for it.

Upon this realization, the film’s beautiful moments stick out to the viewer. Even when Hirayama’s life does change (prompted by the arrival of his niece, who comes to stay with him after running away from her home), there is beauty in his altered, but nonetheless repetitive, routine. This, in itself, is the film. No tantalizing climax or brooding ending, but this is beauty in itself; in forcing the reader to observe, we are awakened by the fascinating.

Remarkably, these revelations were acquired beyond the bar of the subtitles rolling across the screen. Emotions, somehow, go beyond the fascinatingly simple words that we use to communicate. Viewers are often afraid to breach beyond the linguistic world of films in their mother tongue, but Perfect Days is a testament to the beauty that can be uncovered if a theater-goer is a two-parts patient, and perhaps a little brave.