It seems that just 20 years ago, it was far easier to get into college.

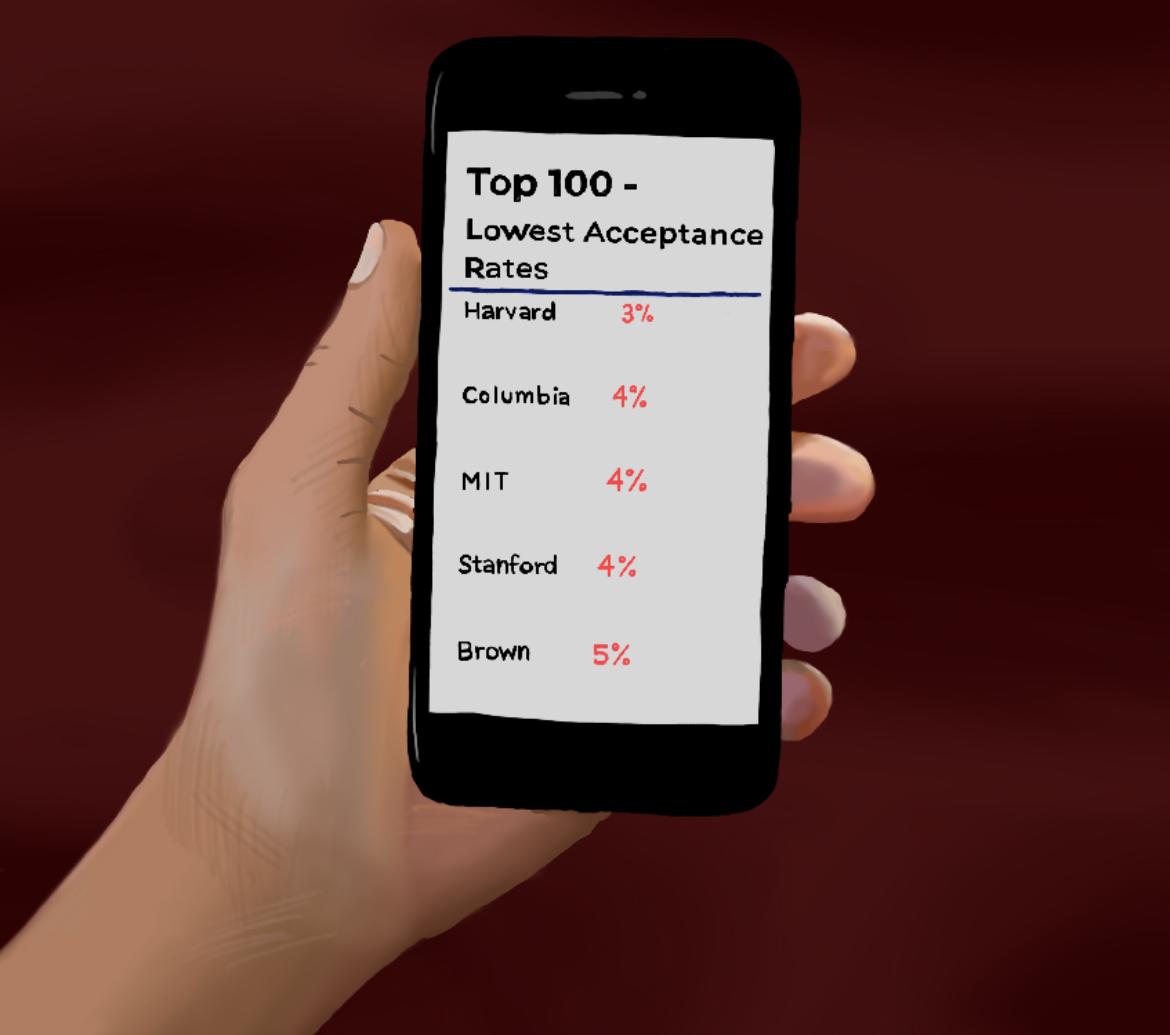

My father applied to college in 1988, when word of universities was not spread over Reddit, Instagram, or anywhere else on the Internet, because finding things on the Internet simply was not a thing. On average, acceptance rates at sought-after universities rested at around 30%, and elite schools were primarily reserved for the wealthy. The “popularity” of a college was nowhere near as much of a driving force in decision-making as it is now. If a college had not managed to reach you through word of mouth, you simply did not go.

Currently, many U.S. universities accept over 50% of their applicants. Yet, according to Education Data Initiative (educationdata.org), as recently as 2021, only 44% of Americans enrolled in a college or secondary institution equivalent. This empirical data reveals a burning fact that many ignore: going to college is a privilege, regardless of which institution you attend. Therefore, when students and parents then speak tempestuously about how college admissions rates are falling rapidly, they are describing a mere minority of America’s institutions and an anxiety that is almost always reserved for the privileged. Yet, in the waves of outrage at selectivity, breeding stress and confusion, the universities with lower acceptance rates almost always reign supreme. Why is that?

Socially, the issue is that many applicants still interpret applying to college as a numbers game dictated by initial glances at low acceptance rates. Brand names, reputation, and prestige all nestle strongly together, triumphing in importance. However, this idea did not materialize in a vacuum; colleges have become products, and much like the objects consumed in other areas of life, the buyers are unknowingly acceding to the orders of the puppet strings of this process. Colleges are businesses– public and private institutions are almost always nonprofit entities but impose exorbitant costs to satisfy customers’ marketing desires.

In 1965, Rene Girard formulated his theory of “triangular desire” in his novel Romantique et Verite Romanesque. The argument posits three points of focus (thus creating the “triangle”): the subject or person desiring the “object,” the desired “love object,” and the mediator or the person who helps fuel the passion of desire in the subject. There are nuances to this idea, and many factors play into what we desire and who we look to when finding it, but essentially, when we see someone else want something, because he wants it, we suddenly want it, too.

In other words, the consensus is driven by a scarcity complex. The number of schools students apply to, on average, has increased, with applicants applying to an average of six schools in 2023, according to Forbes magazine (forbes.com). Students are moved by the acknowledgment of being a big fish in a small–but ironically, international–pond. Admission applications like the Common Application have made it far easier for students to apply to a university. However, instead of judging these institutions based on the quality and rigor of their education, values, or other tangible qualities that prove far more important, popularity is often the primary factor. The shiny and colorful equivalencies in college branding are the scarcity of spots and the illusion of meritocracy. There is a lack of acknowledgment that colleges are basically brand names and that, much like the very way our capitalist economy works, these institutions are a commodity.

Excessively low college admissions rates can be extremely misleading; schools manipulate their yield rates–how many accepted students actually attend a respective school–to affect their rankings. As a result, competition for slots continues to increase. What adds to these neurotic statistics is that US News (usnews.com) is the behemoth of college rankings but is also inversely criticized for often arbitrarily relying on one key factor (much like colleges): money. Although ignored, the social desirability, funding, and manipulation of an institution’s brand is what makes it so popular and, conversely, one of the reasons why more students apply every year.

Most of the time, it seems as though students do not want to acknowledge this; it feels wrong. “How could they have been deceived so deeply?” “Why would these institutions not be genuine?” “Aren’t they here to help raise the next generation of intellectual, candid, and virtuous humans?” When labeled as such, the idea of a subjective popular opinion seems ridiculous. “I, for one, would never be swayed by the arbitrary beliefs of others, for everything that I have ever believed has been something I have formulated myself (wrong), and I am never susceptible to groupthink (wrong again).” Deep in the pits of our strongly knitted egos, we constantly hold that we alone are immune to triangular desire.

Even so, this view is not meant to deface the reputations of the most popular schools and strike them as illegitimate. All of these institutions provide a myriad of resources and opportunities, which are greatly advantageous. But the depth of worry that high school students feel about college is wrongfully placed. They have been pushed into a current of desire perpetuated only by what they have been told, not by their passions or direction. Encouraging students to apply to only a small handful of colleges could help decrease this groupthink, but only on a large scale. On a smaller scale, students can also do individual research on where they would truly like to go. It is time to seek the truth, not follow the herd.