Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki released his twelfth animated film on Dec. 8 under his co-founded studio, Studio Ghibli. The film, called The Boy and the Heron, was a long-awaited release from Miyazaki for many viewers, including myself, as we gazed in envy as it was released in early July in Japan under the title, How Do You Live?

And yet, as I sat down in the theater to watch Miyazaki’s new film, my heart swelled as I saw the signature blue credits screen pop up: “Studio Ghibli” looked down at me in big white letters, accompanied by the studio’s signature mascot, the mythical bear-like creature Totoro, from Miyazaki’s first films. I did not know what to expect; I had isolated myself from any mentions of the film for six months, clicking off of any website I saw where Miyazaki’s name was mentioned because, well, Miyazaki’s films are essentially sanctified in animation.

The film was scored by Joe Hisashi, a Japanese composer who has worked alongside Miyazaki for all 12 of his films and has a musical style unlike any other artist I have encountered. Inspired by composers such as Mozart and Bach, Hisashi brings a thoughtful musical element to Miyazaki’s films, deepening his narratives with orchestral arrangements that make the audience lean deeper into their seats. With powerful visuals accompanied by equally powerful music, emotions begin to rise, and viewers are absorbed into a wonderful, fantastical dream.

The film begins with tales of World War II, during the Pacific War (the portion of WWII fought in eastern Asia). Miyazaki was born in 1941, three years after the war had begun, and his films reflect the experiences he led as a child in turbulent Japan. The film follows a 12-year-old boy, Mahito Maki, whose mother is killed in a hospital fire. The first few scenes begin with the same peace expected of a calm summer night, but when Mahito wakes up from a deep sleep to the news that the village hospital is on fire, the film picks up its pace. A swift change in pace is something Miyazaki effortlessly does in his films: the music begins to swell with tension as Mahito runs through the village streets toward the hospital. The village people are distorted; they too represent Mahito’s fear. A visual pathetic fallacy, Mahito stares in horror as the hospital is engulfed in flames. After the accident, Mahito moves to a new home with his father (who has now married Mahito’s mother’s sister, Natsuko). In the Japanese countryside home, he soon discovers a gray heron in the backyard who seems rather preternatural.

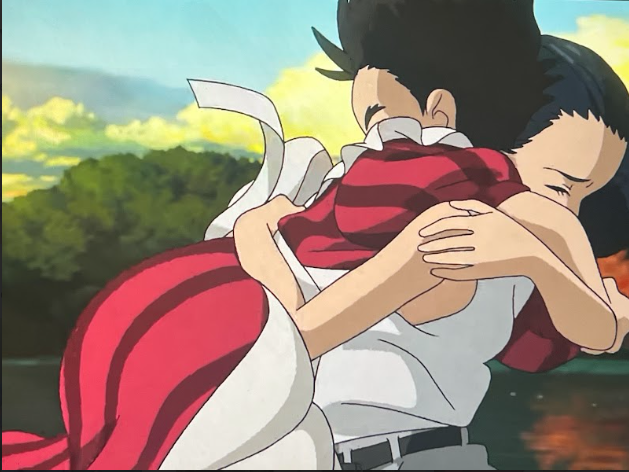

Though the film may initially seem like a work of historical fiction, its fantastical elements catch the viewer suddenly. The gray heron is more than just a garden regular, and his character reveals the fantastical nuances of the film. Suddenly, Natsuko goes missing. Trying to find her, Mahito ventures into the forest where she was last seen. Accompanied by one of the older housemaids, Mahito uncovers an entirely different world below the one he had known, and his original goal of finding Natsuko develops more depth: he must also find his mother.

Thus, the film takes on a popular narrative — “the hero’s journey,” in which a main character must embark on a voyage towards an end goal and, by extension, find out more about himself and others. Thus, The Boy and the Heron becomes more than simply a story about a boy; its writing develops philosophical reflection that makes the viewer introspect.

But even in moments of solace, Miyazaki possesses the unique ability to make the ordinary extraordinary. This is particularly shown through the film’s softer sequences; the housemaids boil a stew, or Mahito eats a tart with jam and butter for breakfast. “Ghibli food” — a stylistic staple that countless chefs all over social media have tried to replicate — is one of a kind. The landscapes created by the Ghibli animators are also a testament to Miyazaki’s eye. Green, swaying fields with clouds passing overhead are no longer mundane but a testament to the beauty of the natural world. An attention to detail is what adds presence to his films, for beauty is all around us.

The Boy and the Heron also reflects Miyazaki’s films’ relations in that they are wonderfully progressive. Though Miyazaki is 82 and wears the same apron as he did 30 years ago (he was also quoted in a New York Times interview saying that he drives the same fuel-sputtering car as he did in 1980), his films are the spitting image of progression. This can perhaps be seen most saliently in the fact that he writes his female characters with as much depth as their male counterparts, a quality much of the globalized media that we consume seems to fail at doing, again and again. But Miyazaki’s female characters are beautifully headstrong; take one of the maids who work at Natsuko’s estate, for example. Kiriko, an old woman who accompanies Mahito on his fantastical journey, is clever and humorous. At the film’s beginning, she tries to convince Mahito that she has a much better bow and arrow than the one Mahito childishly fabricates from natural accouterments, but only if he finds her a box of her favorite sacred (but scarce) cigarettes.

Beyond the depth of Miyazaki’s female characters, he is also highly adept at writing children. Teenagers and kids make up the bulk of Miyazaki’s main characters, perhaps because they are the best figures to convey fantastical stories, with their sense of wonder still intact. Yet, Miyazaki shows his own ability to stay curious through his well-written young characters; they are smart and passionate, often going against what the adults (who seem like they have lost all of their hope) tell them. Mahito is no exception; his curiosity leads him to his discovery of this fantastic world below, and his kindness connects him so deeply with all of the other characters in the film. Mahito is tender with his emotions, and the relationships that he cultivates make him easy to root for as a main character.

As the film continues, Mahito’s journey raises many questions about the nature of our world. Perhaps Miyazaki had done a lot of reflection while writing this movie, too (he is an avid reader and writer; I wouldn’t be surprised). The Boy and the Heron makes artful use of 124 minutes, proving to inspire those with a sense of wonder. Perhaps if our world was a little bit more like that of Miyazaki’s, the joy we once had as small children would still be present in the tired adults of our world.