It has been nearly five months since COVID-19 was no longer declared a pandemic. In terms of schools being back in person and jobs and buildings reopening, the world has been doing its best to move past what proved a challenging time.

When many think back to the virus that began to spread over three years ago, they are reminded of the strength and perseverance of healthcare professionals. Ranging from doctors to nurses to secretaries, professionals in this field certainly felt the brunt of the pandemic. Working long hours, wearing head-to-toe gear to stay protected, and going weeks without seeing loved ones are only a few of the hardships endured. Senior Isabella Martinez explained, “[Healthcare workers] saw numerous people lose their loved ones and had patients who they just couldn’t help fight COVID. Seeing that whenever they went to work must have harmed them both physically and mentally.”

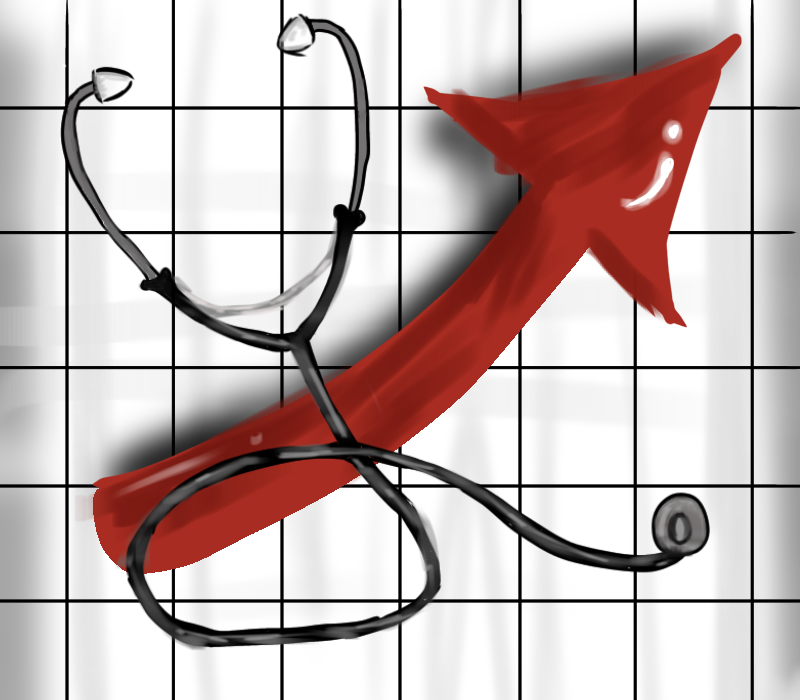

In the study “Suicide Risks of Healthcare Workers in the U.S.” on the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) website (jamanetwork.com), researchers questioned if healthcare workers are more prone to suicide than non-healthcare workers. After designing a cohort study in which they separated healthcare workers into six groups (practicing nurses, physicians, etc.) and pulled a sample of workers from an American Community Survey linked to the National Death Index records, they concluded that their hypothesis was correct: There is now an increased risk of suicide for healthcare workers in the U.S. Because of this, “New programmatic efforts are needed to protect the mental health of these U.S. healthcare workers,” the study found.

This study has caught the attention of many news and media outlets, which are now bringing up the discussion of how to appropriately attend to the needs of the healthcare workforce. Judy Davidson, a nurse scientist at the University of San Diego in California, discussed the issue with CNN in the article “U.S. Healthcare Workers Face Elevated Risk of Suicide, New Study Finds.” In this article, Davidson said, “The new study findings place ‘an urgent need’ for healthcare executives to re-examine the wellness programs they offer to their staff to assure that workers have a safe pathway to access mental health treatment.”

School psychologist Jordan Richman shared his thoughts: “I think the pandemic certainly changed the way counseling is delivered, with more practitioners moving to Zoom or telehealth. This seems to have become more of a normal method of service. Whether this is a good or bad thing can be debated,” he said. “In general, it seems the pandemic has further increased a tendency for people to socialize less and be more isolated in their homes,” added Richman. When asked what could be done to help healthcare workers, Richman said, “At the heart of resilience is the ability to cope with stress. Coping skills are essential in dealing with life’s challenges, and developing these skills in counseling may be beneficial.”

Moreover, the outcomes of these studies have given reason to the recent rise in strikes in the healthcare field, namely, the three-day-long strike initiated by health care giant Kaiser Permanente.

From Oct. 4 to Oct. 7, the Kaiser Permanente company organized strikes across California, Colorado, Oregon, Washington, and Virginia because of understaffing and pay. Considered the largest healthcare strike in history, with over 75,000 Kaiser Permanente employees participating, the strikes ended, or paused, as the company has agreed on negotiating a new and fair contract.

This strike simply illustrated the pressures healthcare workers have been facing and that many have overlooked for some time. Junior Catherine Christakos stressed, “There is a direct correlation between the pandemics and job burnout, especially because of the increase in work hours. Nurses specifically were working 40+ hours a week and dealing with patients in critical condition, all while being paid less than they should be.”

These difficulties are why healthcare companies and the government are investing time into developing resources for healthcare workers, mainly mental health resources. The main goal is to make sure there are hubs that can provide one-on-one support to a worker in need. Going about how to best implement these tools nationwide is still being explored.

COVID-19 struggles still linger within society, especially in the healthcare system. There is a shortage of healthcare workers today, and hospitals still continue to cut staff. While there are also economic factors that play into why this is the case, a top concern is how to attend to the mental health needs of active healthcare employees who long shifts and provide care for many patients.