Anatomy Students Watch Successful Kidney Transplant

Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

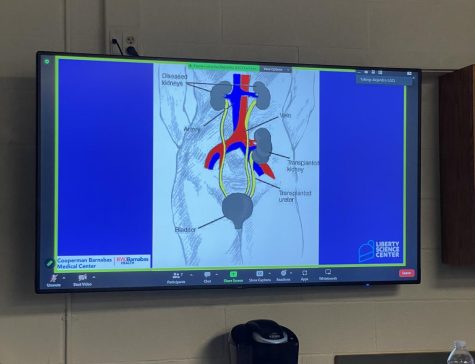

Students in Jon Zaccaro’s Anatomy and Physiology classes recently viewed a life-saving surgery in the Innovation Center. Broadcasted by the Liberty Science Center in New Jersey, a kidney transplant from a 38-year-old sister to her 43-year-old brother was shown. Students were able to see how a kidney is extracted from a donor, sterilized once extracted, and finally donated to the recipient. “As a future pre-med student, I thought it was a great way to cultivate my passion for the subject,” expressed senior and anatomy student Ethan Palacio.

The broadcast began around 9:00 a.m. with representatives from the Liberty Science Center (LSC.org) and the New Jersey Sharing Network (NJSharingNetwork.org)—the official organ procuring organization of New Jersey—as well as a previous kidney donor. Because the surgery was prerecorded, the representatives and the donor began the presentation talking about organ donations and the great need for them in America. “There are 100,000 individuals waiting on life-saving organs; eighty percent of those are waiting on kidneys,” Ametra Burton from the New Jersey Sharing Network explained on the broadcast. “Every organ donor has the ability to save eight lives, and tissue donors can enhance the lives of up to 75 people.”

Rudy DiGilio shared his story of donating his kidney to his brother, whose health was failing rapidly. Almost four years after that surgery, DiGilio and his brother both lead happy, healthy lives; DiGilio explained on the broadcast that once a recipient receives a kidney, “within a few hours a person’s health improves dramatically. The kidneys want to work.”

Since kidneys are responsible for cleaning and filtering a person’s blood several times each day, failure of one kidney to work properly can be fatal for an individual’s health. A kidney transplant, then, is the most frequently used method of treatment; however, there are several steps and precautions that must be taken to ensure that the kidney donated is going to be accepted by the recipient’s body and function properly. Compatibility tests, such as blood typing and tissue matching, are done to see if the antigens of the donor’s kidney—or the protein markers on internal viscera that tell one’s immune system that a substance is harmless and belongs in the body—match up with the recipient’s antigens. If the antigens fail to match, agglutination, or blood clotting, can occur.

A recipient’s body could also attack the donated kidney if the match is incompatible, seeing it as a threat to the body. This is why donations between siblings and closely related family members—like the donor and recipient of this surgery—are statistically more successful. The more closely related the donor is to the recipient, the more likely the antigens will match; siblings have a one in four chance of being compatible for an organ transplant.

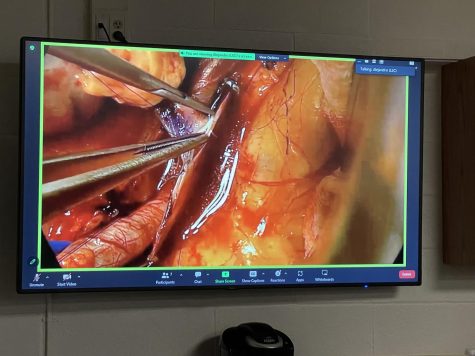

The virtual experience lasted about an hour and a half and was split up into three phases: extraction of the donor’s kidney, sterilization of the kidney, and transplantation into the recipient. “I liked that this surgery was narrated, with someone explaining the whole process at each step,” commented senior and anatomy student Kate Chiulli. The donor’s surgery was brief, with little blood loss due to laparoscopic technology, which allowed Dr. Stuart Geffner to operate on the donor while making as little incisions as possible. After the donor was brought into the operating room, an insufflation tube was inserted into her stomach, filling it up with carbon dioxide gas. This provided room to insert several trocars—or robotic probes that had video cameras attached to them—into her abdomen. Once her intestines were moved aside, Dr. Geffner could manually control the trocars and start to harvest the renal artery, renal vein, and ureter of the kidney. This would then isolate the kidney, allowing Geffner to extract it from the donor.

Several instruments were used throughout the surgery to ensure minimal blood loss. A harmonic scalpel—an instrument that vibrates back and forth to produce heat to avoid bleeding when cutting through skin—pushed aside membranes and connective tissues outside the kidney and its blood vessels. In addition, a straight angle clip gun was used to simultaneously cut and clip shut the renal artery and vein. The clips from the device were made of bioinert, nonmagnetic metal, so they will never dissolve in the donor’s body, nor be detected by a metal detector.

Once the renal artery, renal vein, and ureter were harvested, Dr. Geffner used a scalpel to increase the size of the incision. Geffner had to do so very carefully: If he cut the skin too deeply, some of the CO2 gas could have escaped the donor’s abdomen, thereby decreasing the space he had to work with. At the same time, the anesthesiologist filtered heparin, a blood thinner, into the donor’s body to ensure little blood loss. Finally, the kidney was placed into a specimen bag, removed, and placed straight into a solution known as sterile slush, keeping the kidney cold and clean.

After the kidney was removed from the slush, phase two of the surgery could begin. The kidney was first flushed out with sterile solution to avoid blood clotting, which could hinder the kidney’s filtration ability. Excess tissue and fat were also removed, and the arteries and veins were sutured—or sewed up—and filled with saline solution. After all that, a sterile sharpie was used to draw a visual reference line to help position the kidney correctly in the recipient’s body to avoid circulation issues in blood vessels.

Finally, phase three—the recipient’s surgery—could begin. Unlike the donor’s surgery, the recipient needed a traditional open incision to expose his abdominal area. The donated kidney needed to be placed further down below his malfunctioning kidney; this was done to minimize blood loss and cut down on incision complications. First, the renal artery and vein needed to be matched up with and grafted onto the recipient’s iliac artery and veins, which were cut open by a microscalpel and a circular hole punch and then clamped shut to avoid excess bleeding. Once that was completed, any excess blood and fluid was flushed out of the incision area.

After the area was cleaned out, the kidney was permanently sutured to the recipient’s blood vessels. The iliac veins were unclamped, and any excess holes in the vessels were also sutured. Finally, to test that the donated kidney was working properly, the ureter tube was squeezed to ensure that urine is being produced. The ureter tube was then connected to the recipient’s bladder, and protamine was administered into the donor to counteract the effects of heparin.

That final step brought the surgery and presentation to a fitting finish. “It was a very informative experience, and it helped to enhance my knowledge of the urinary system!” exclaimed Chiulli.

“It was a very exciting and interesting presentation that has certainly caused my love of science and medicine to grow,” Palacio expressed. “I one day aspire to be a physician, and so seeing doctors in action has allowed me to gain a critical understanding of how members of a hospital can work together in order to save a life.”

By watching the surgery and hearing DiGilio’s transplant story, many anatomy students considered the possibility of donating a kidney to a person in need. “Knowing that I could save someone’s life that I love and care about, donating a kidney would be completely worth it,” explained junior and anatomy student Sabrina Ostroff.

“Before the surgery, I probably would’ve said no, but now, since I know the facts about how much kidneys and other organs are needed, I might consider it,” expressed junior and anatomy student Chloe Singh.

“I did enjoy hearing from the donor and thought listening to the experience from his perspective was able to broaden my understanding of the procedure,” Palacio remarked.

Thus, the experience of viewing a kidney transplant was beneficial not just from a medical standpoint, but from a humanistic perspective too, as all have the ability to save a life. “Even if I didn’t know the person, I would know that I would not only save the person, but their family as well,” said Ostroff.

I am a member of the Class of 2023 and the Driftstone editor-in-chief. Along with creative writing, I enjoy spending time with family and friends, getting...